A Guide to Every Permitted Natural Gas Well in West Virginia

by Al Shaw, ProPublica and Kate Mishkin, The Charleston Gazette-Mail, March 6, 2019

This article was produced in partnership with the Charleston Gazette-Mail, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

Since the rise of hydraulic fracturing made it possible to get to the rich layer of natural gas in the Marcellus Shale, the number of horizontal well permits — which allow producers to drill for miles underground in all directions from a single point — has increased dramatically in West Virginia.

As of 2006, the state had issued only a dozen total horizontal well permits. As of last year, that total had reached over 5,000, according to data from the state's Department of Environmental Protection.

Find West Virginia horizontal well permits near you

How to read the map

Natural gas well permit and operator name

——

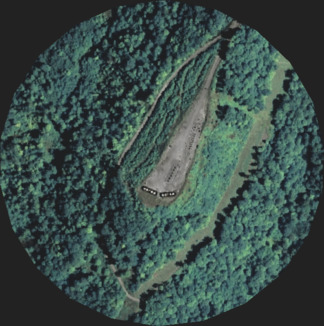

Approximate extent of permitted underground horizontal wells

————

Buildings

———————————

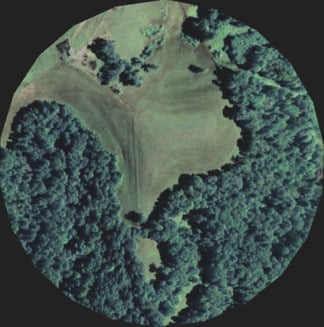

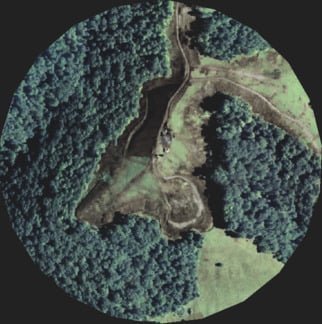

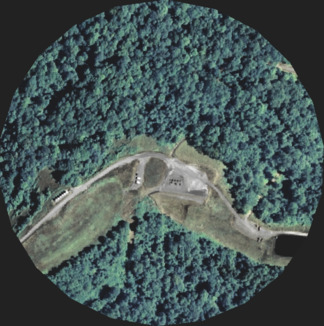

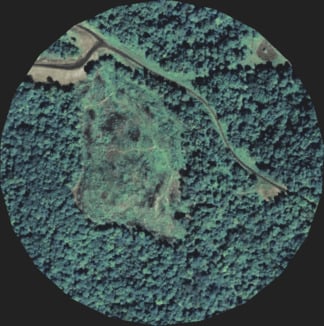

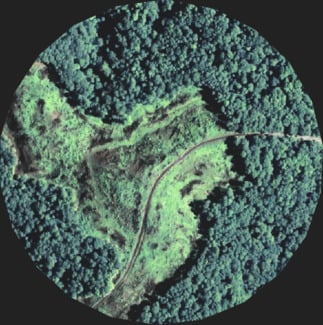

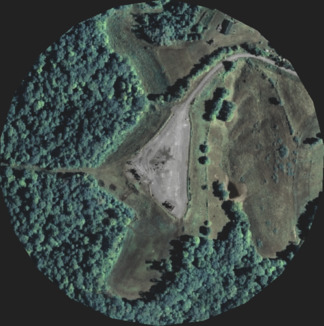

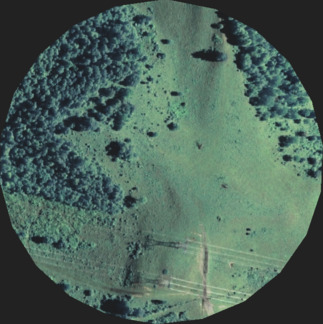

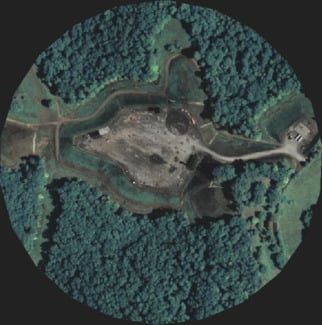

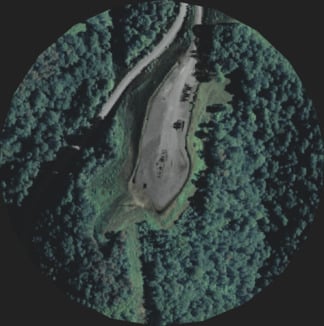

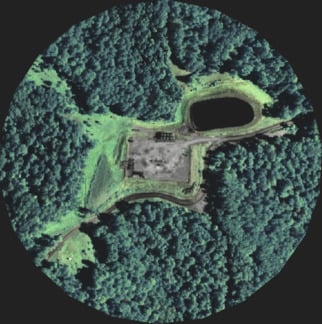

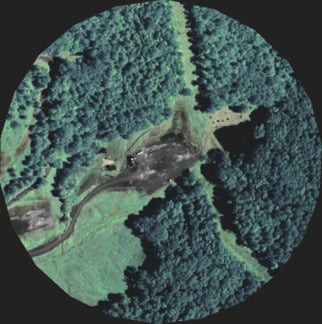

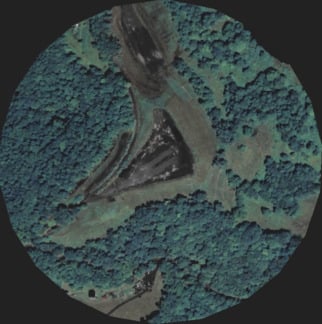

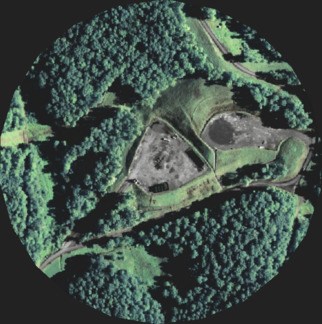

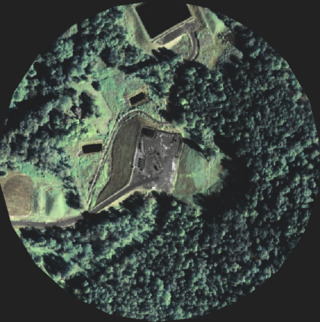

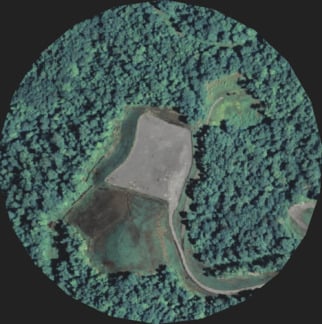

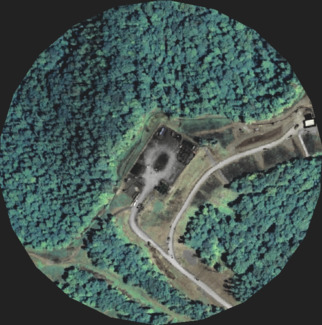

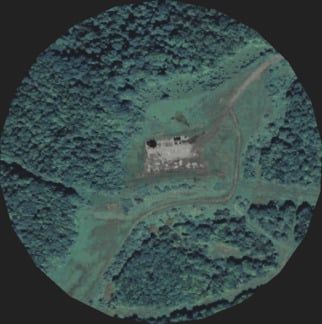

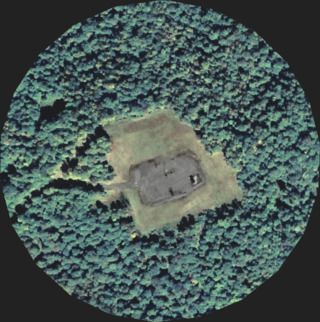

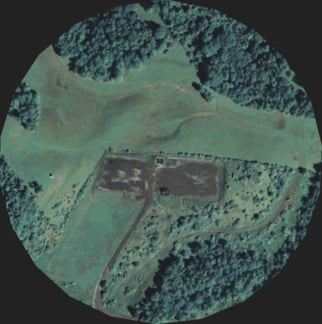

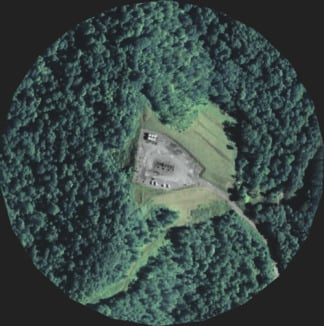

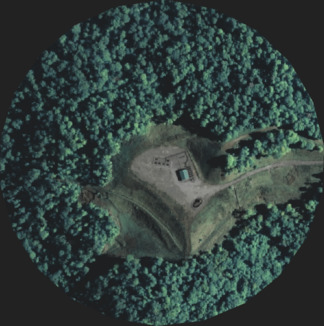

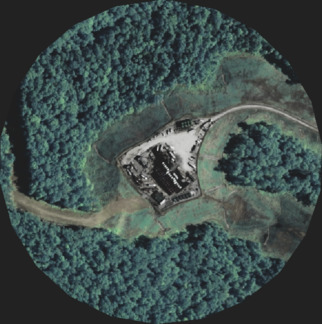

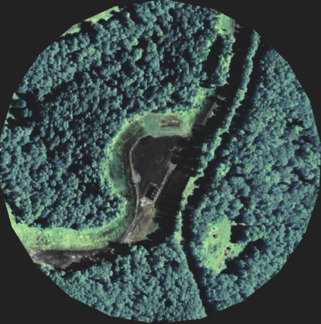

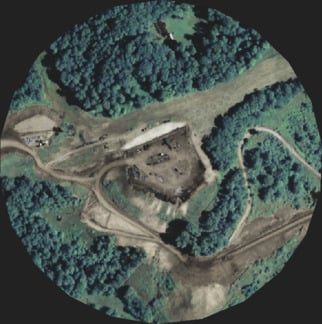

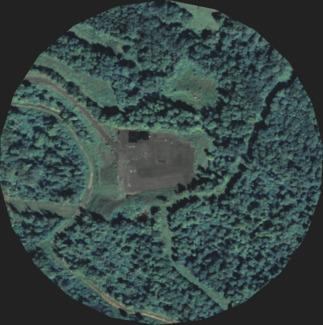

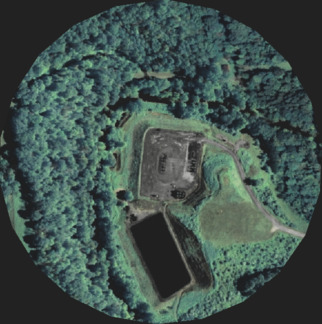

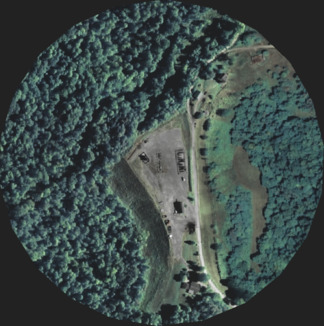

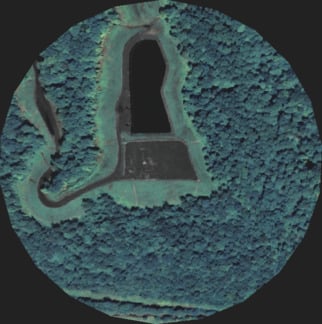

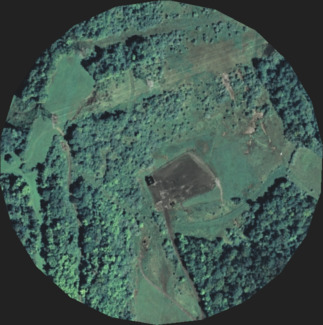

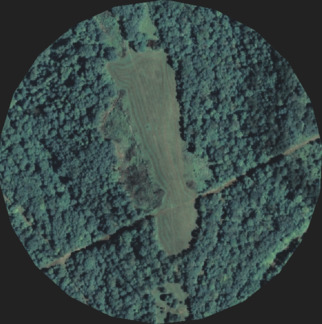

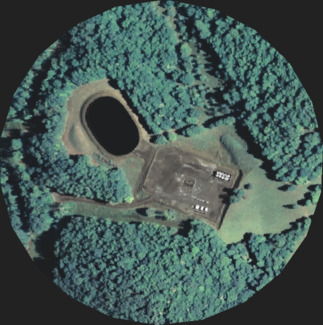

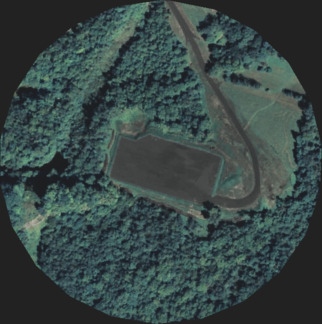

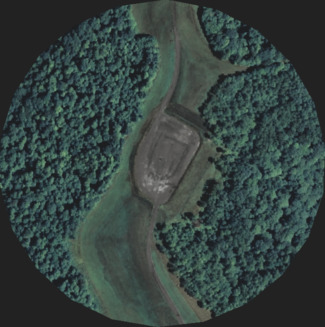

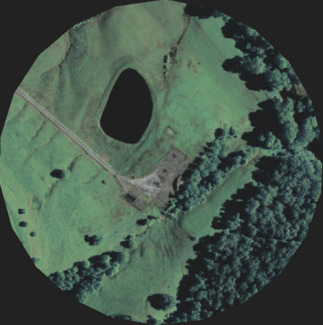

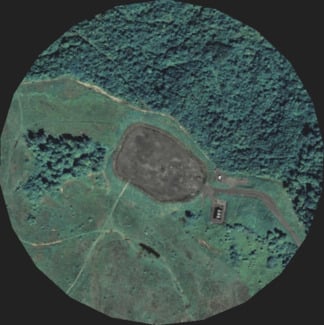

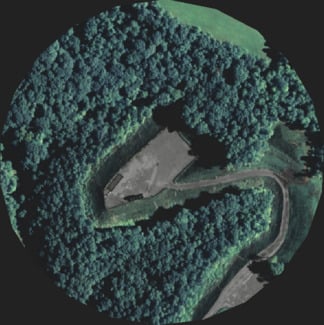

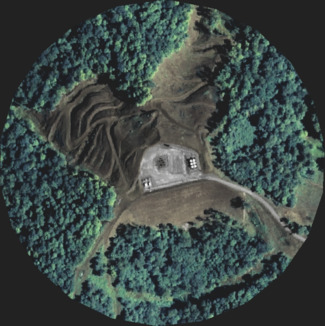

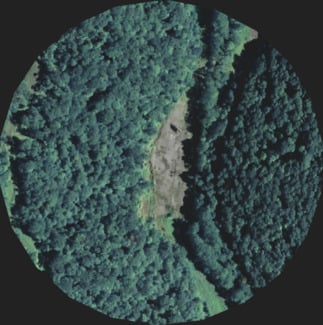

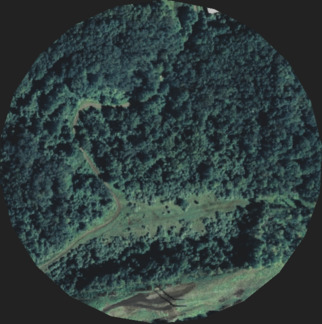

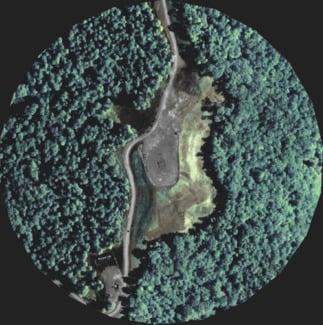

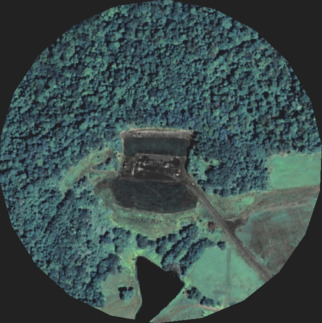

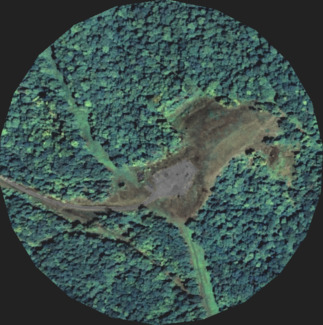

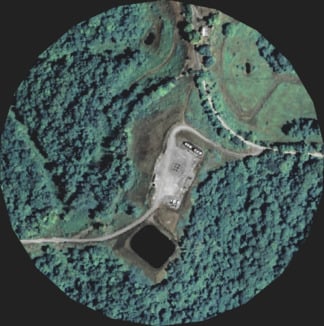

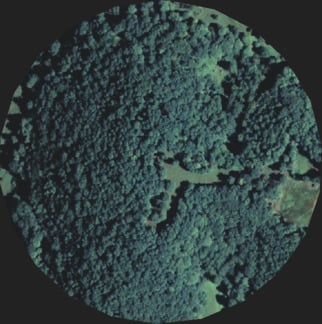

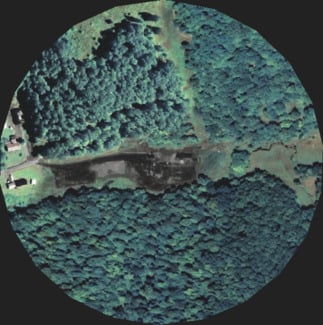

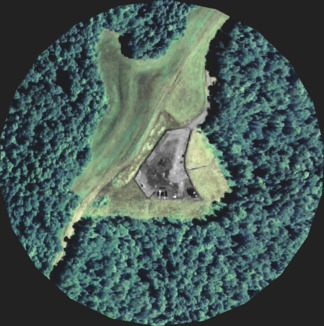

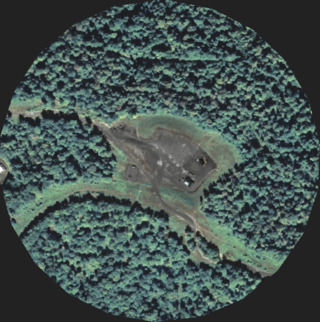

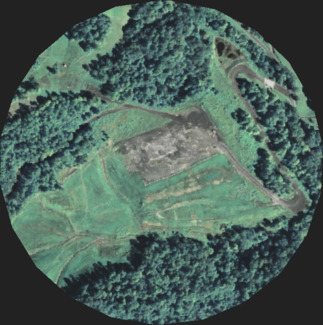

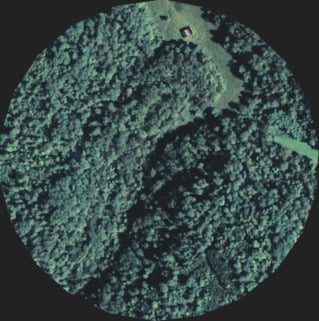

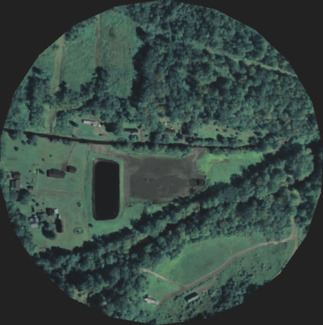

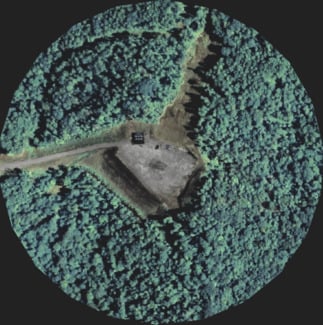

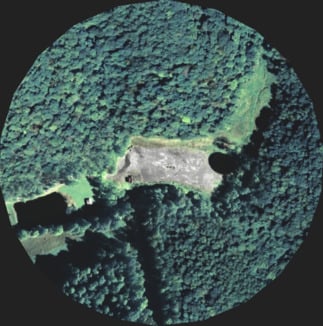

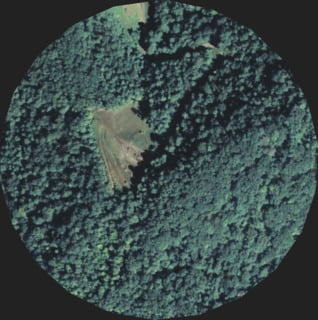

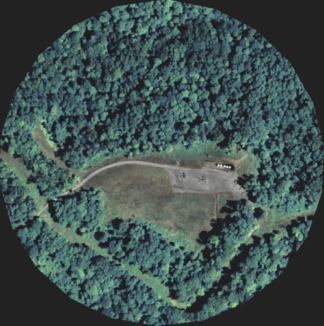

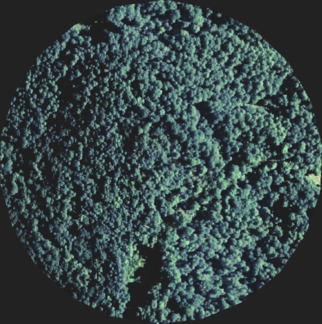

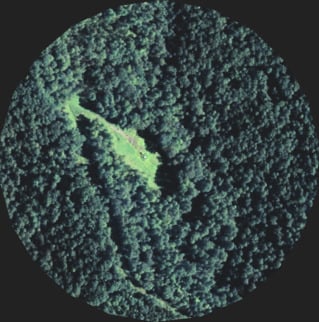

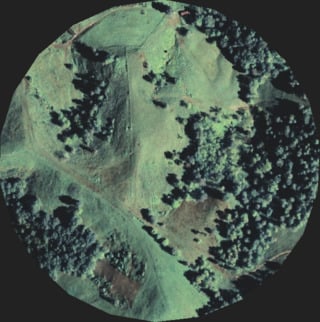

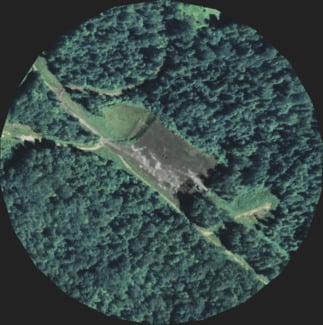

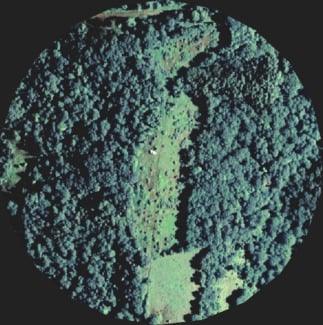

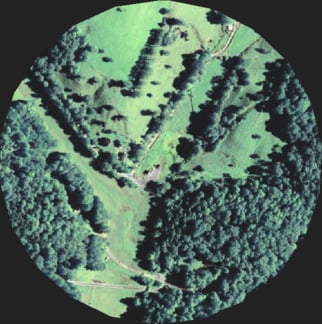

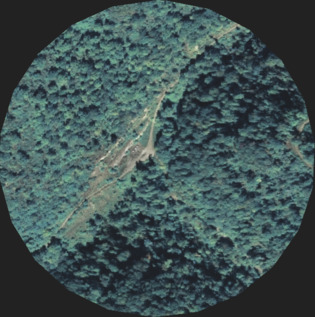

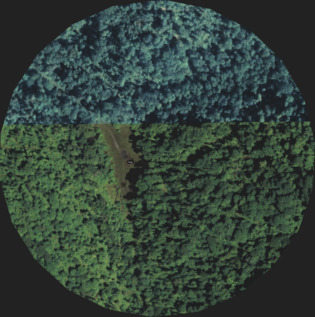

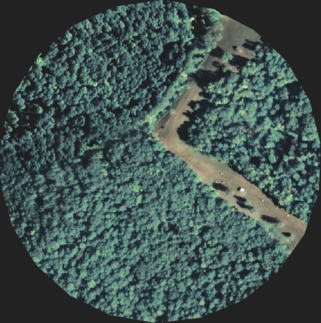

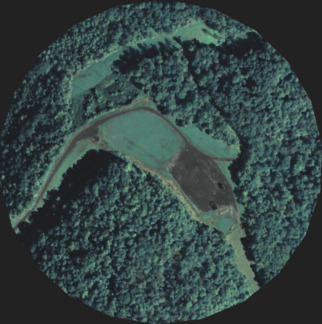

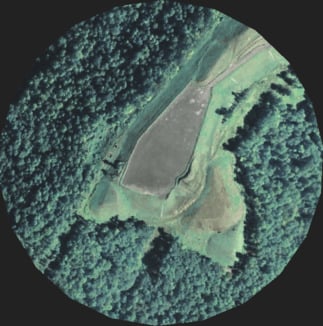

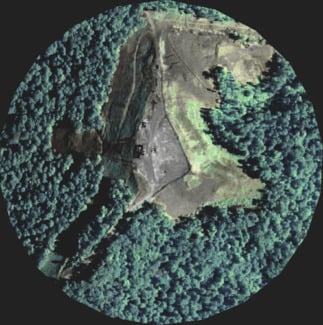

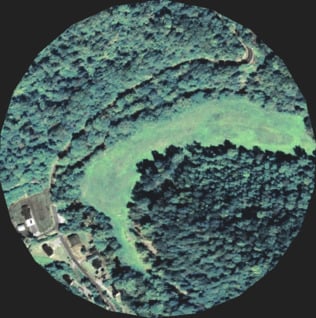

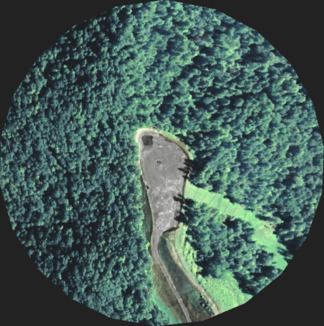

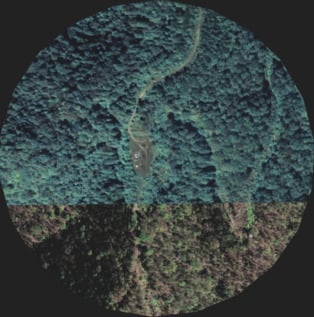

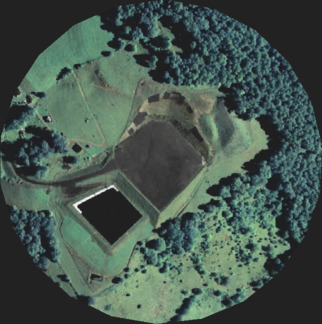

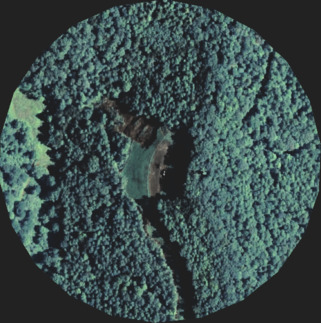

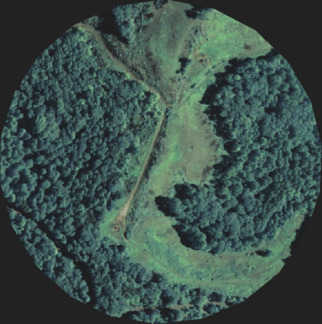

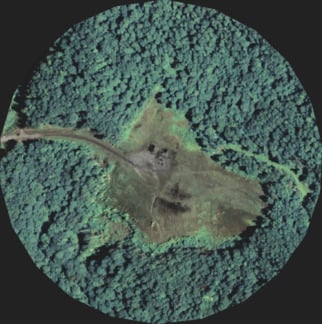

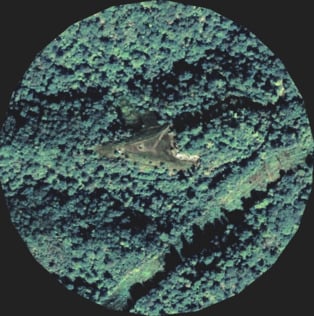

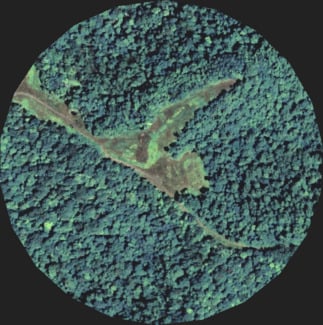

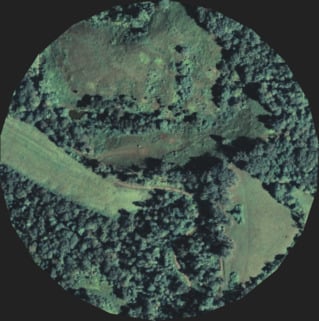

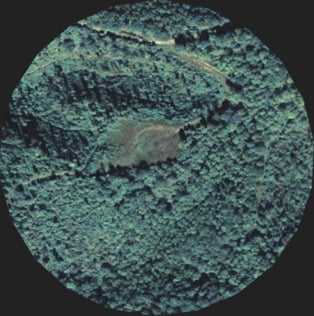

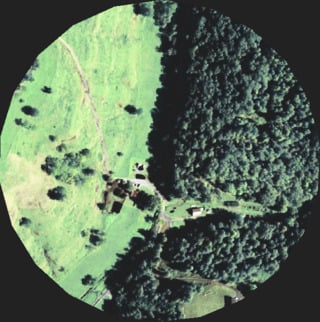

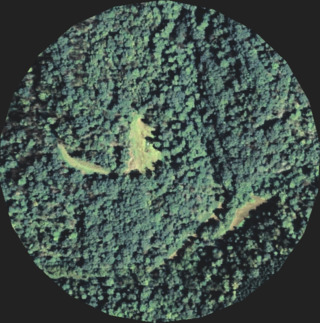

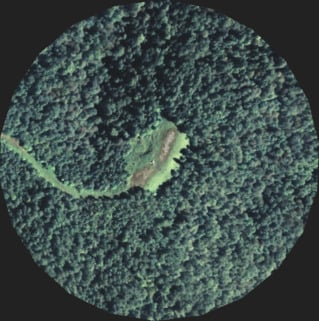

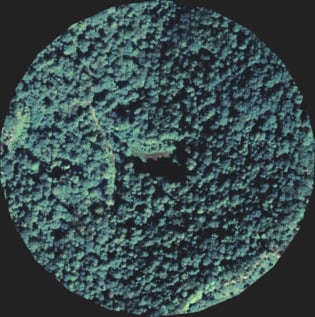

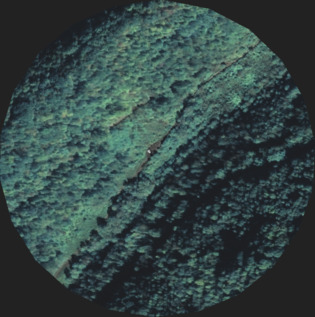

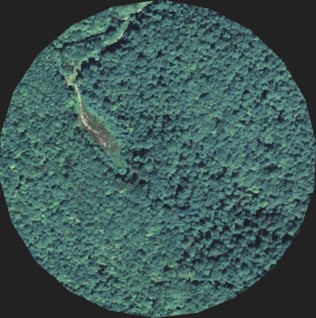

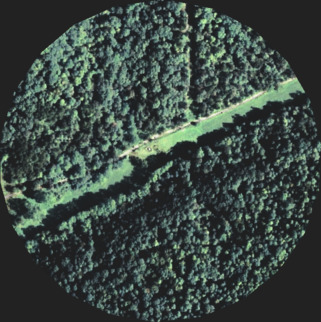

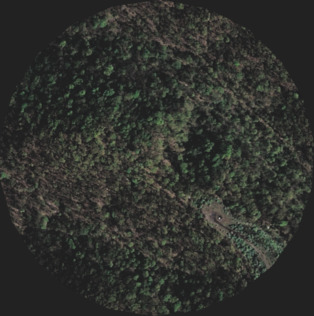

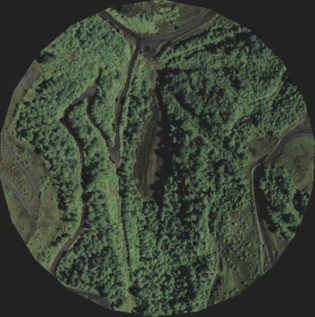

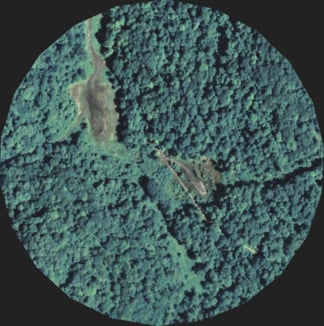

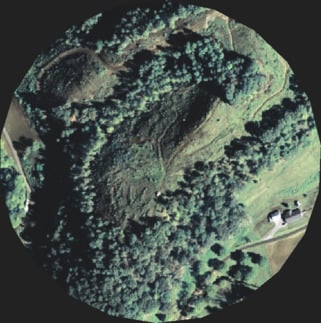

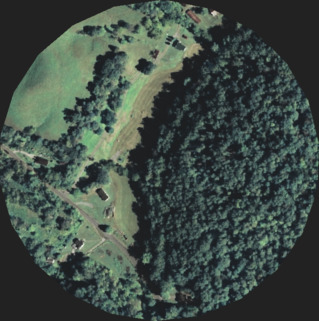

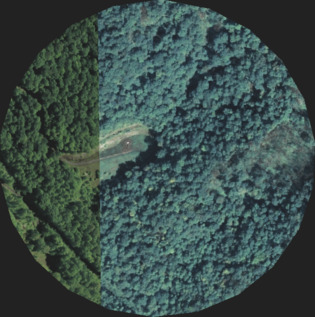

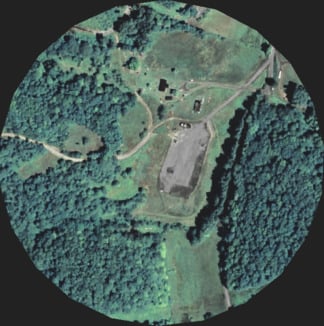

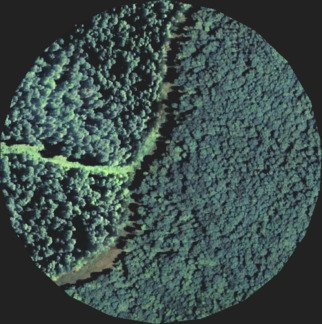

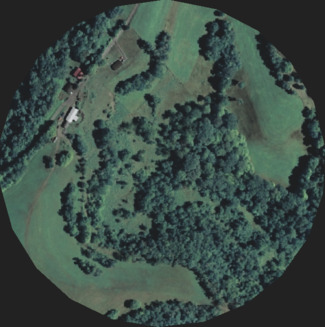

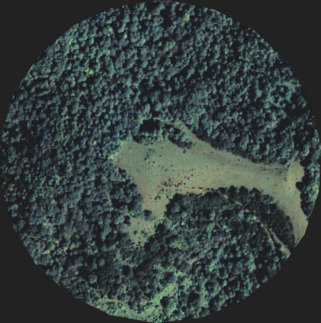

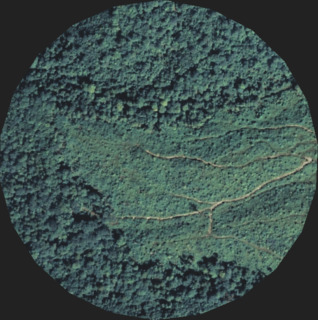

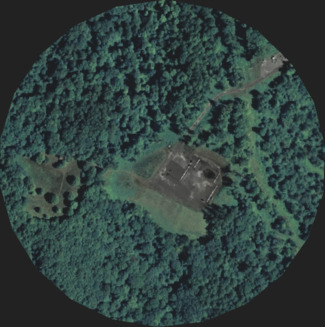

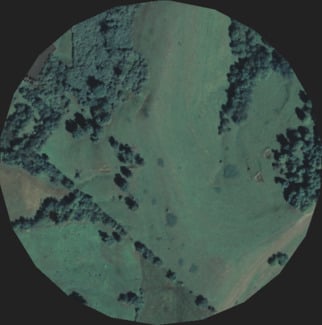

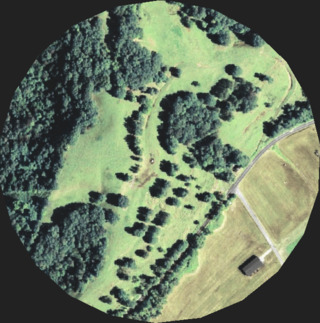

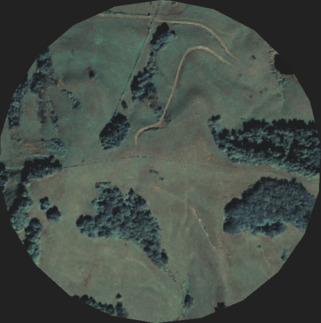

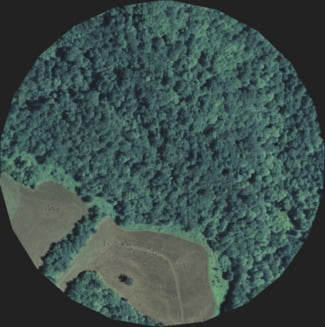

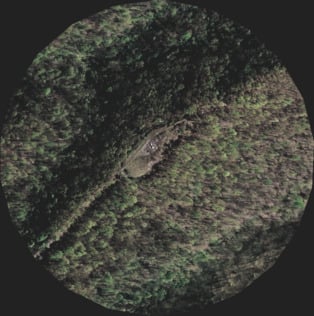

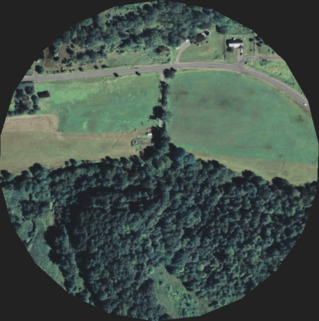

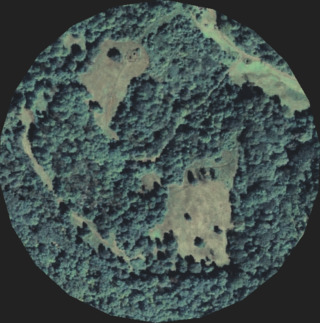

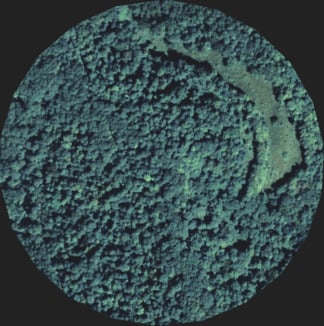

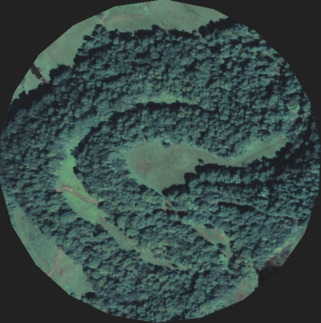

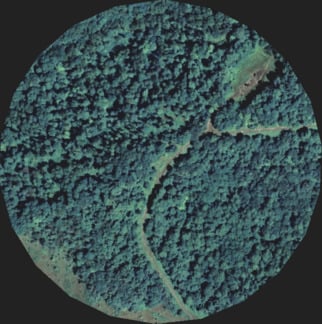

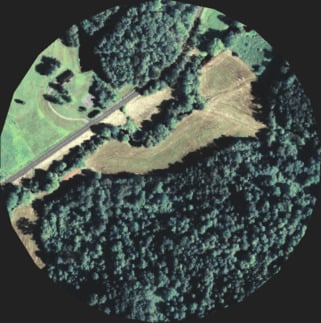

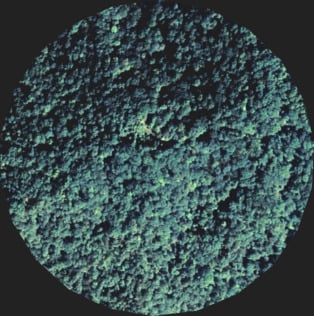

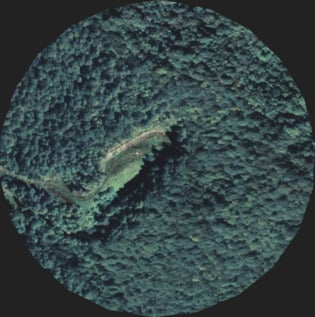

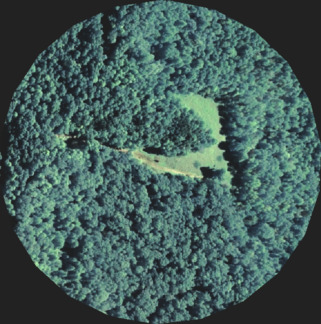

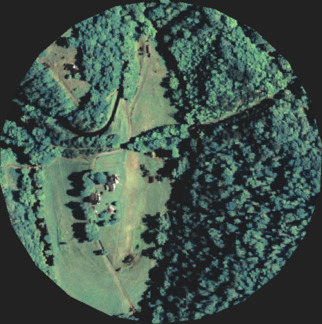

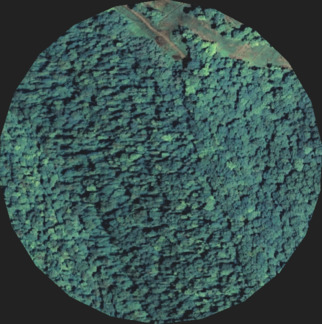

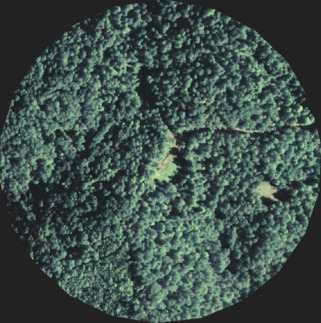

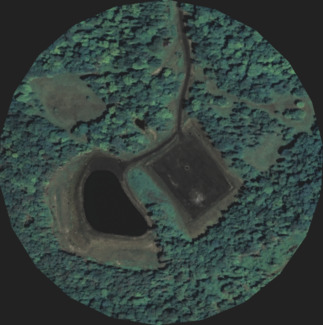

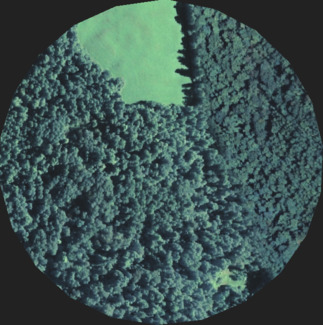

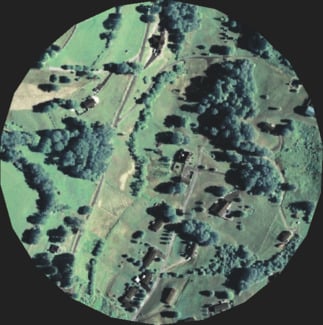

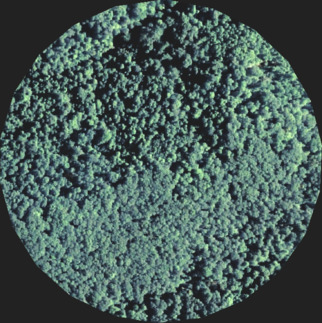

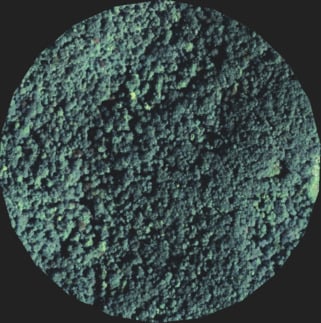

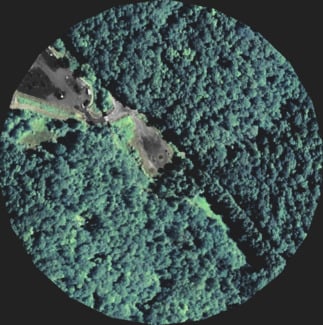

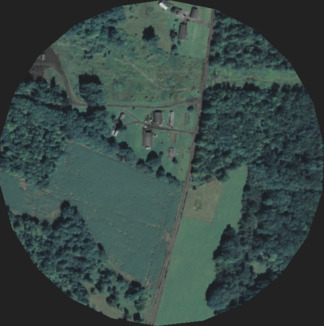

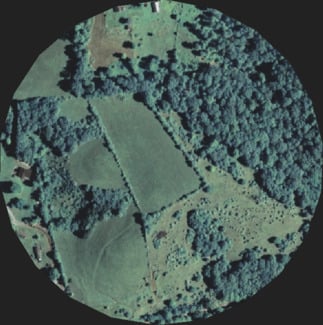

Accessing natural gas in West Virginia's mountainous terrain is much more complicated than in flat Texas or North Dakota. To build horizontal wells, gas producers must first clear the landscape for well pads, which are large, gravel clearings over acres of continuous open space. For the first time ever, ProPublica and the Gazette-Mail used software to show as many as 1,500 well pads, located on the forested hilltops and valleys of Wetzel, Doddridge, Marshall, Harrison and a handful of other counties along the state's Marcellus belt. Here's what they look like.

This pad in Wetzel County is permitted for 20 horizontal wells

Well pads are large gravel clearings where horizontal natural gas wells are drilled into the earth. In West Virginia, this often involves flattening hilltops, denuding forests and paving new roads. There can be multiple wells on a pad. Some have over a dozen. ProPublica obtained images of every permitted horizontal well pad in the state using data from the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection and aerial imagery from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Read our full methodology ↓

Until 2011, there weren't many restrictions on where natural gas producers could put well pads. The law at the time only prohibited wells within 200 feet of homes and water wells. They're built next door to homes, schools and drinking water intakes. Loud drilling can go on for months at a time, and large semis drive to and from well pads around the clock.

In 2011, the West Virginia Legislature passed the Natural Gas Horizontal Well Control Act, which increased restrictions for natural gas well pads. Under the new law, pads had to be at least 625 feet from an occupied dwelling and could not be placed within 250 feet of a water well or stream. But the law didn't require buffer zones between sensitive areas like schools or public lands, and it measured the 625-foot buffer from homes from the center of the well pad, meaning the pad itself could end up much closer than that to dwellings.

Even under the new rules, people who live near natural gas development still bear the burden of hundreds of trucks a day driving past their homes to pad sites or the constant din of drilling that can ricochet off hilltops into valleys miles below.

This year, Delegate Barbara Fleischauer, a Democrat from Monongalia County, sponsored legislation to increase that buffer to 1,500 feet between a well pad and a home, but it hasn’t advanced in the Republican-controlled chamber.

In West Virginia, the person or entity that owns the land's surface may differ from who owns the mineral rights underneath. In such cases, drillers have the right to access their minerals in a "reasonably necessary" way, and they can often build well pads against the wishes of farmers who own the land they're built on.

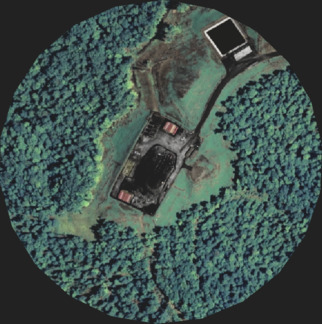

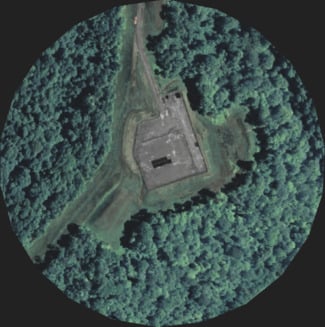

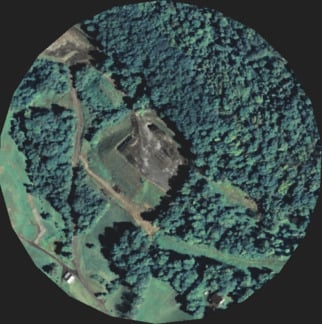

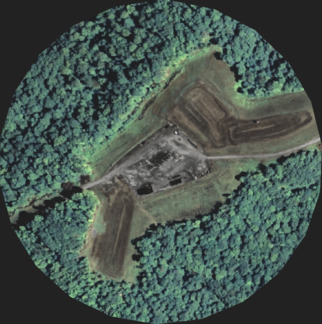

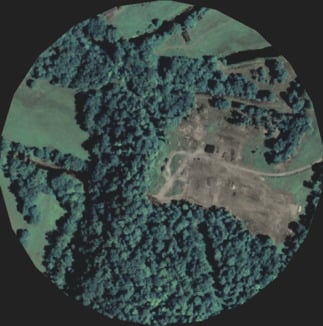

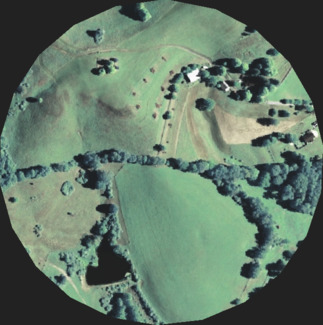

More than a dozen horizontal natural gas wells can be drilled from a single well pad, like this one in Doddridge County. (Mayeta Clark/ProPublica and Chuck Burkhard/Drone Imageworks for ProPublica)

But lawyers for residents argue that gas industry has expanded its operations to the point where the impacts are no longer "reasonable" or "necessary." Two cases brought by groups of residents who live near well pads are going before the West Virginia Supreme Court this year. In one case, lawyers for a group of families in Harrison County argued in January that their clients can't sleep at night or sit on their porches because of constant bright lights and dust from Antero Resources Corp.'s drilling operations and constant truck traffic. The case centers around 24 wells on six well pads in the Cherry Camp area near Salem, West Virginia. Lawyers for the Harrison plaintiffs say that this kind of development was never contemplated when mineral rights were sold a century ago.

Lawyers for Antero wrote in a court filing that the residents "offered no evidence that Antero exceeded the scope of its property and contractual rights by impacting Petitioners' surface estates beyond what is reasonable and necessary to develop its mineral leasehold."

Moreover, as horizontal drilling technology gets better, well pads are getting bigger. A 2017 analysis from the environmental consulting firm Downstream Strategies found that well pads grew from 1.6 acres, on average, to 2.4 acres between 2007 and 2014.

Over 5,000 horizontal well permits have been issued in West Virginia since 2004

Horizontal well permits are clustered in a handful of West Virginia counties

Legislators and industry lobbyists point to the natural gas boom as an engine of job growth for the state. But a report from the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, called “Falling Short,” outlines the ways the state has failed to live up to great expectations.

According to the report, the state’s six largest-producing gas counties lost around 1,600 jobs during the gas price crash from 2014 and 2016, even as natural gas production was increasing. Those counties saw some gains in 2017 when gas prices bounced back, but the cycle shows how the pivot to gas exposes West Virginia to a similar boom-bust economy as it experienced over the decades with coal, said the report, co-authored by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

“Shale development is not yet translating into long-term economic gains for these counties,” the report said.

Correction, March 11, 2019: This story originally misstated in one instance the number of horizontal well permits issued by West Virginia. The state had issued a dozen permits as of 2006 and over 5,000 total as of last year, not a dozen permits total in 2006 and over 5,000 last year.

The Charleston Gazette-Mail and ProPublica want to tell the story of the changing landscape in West Virginia, and how coal and natural gas are impacting it. West Virginians: Tell us how your community is changing. Call or text us at 347-244-2134, or email us: [email protected].

Kate Mishkin covers the environment, workplace safety and energy, with a focus on coal and natural gas for the Charleston Gazette-Mail. Email Kate at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter at @katemishkin.

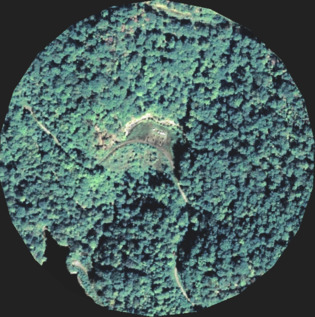

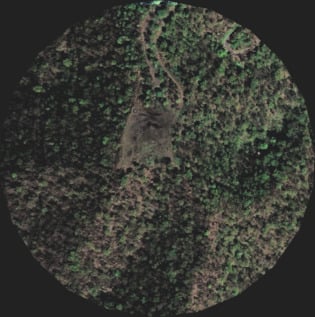

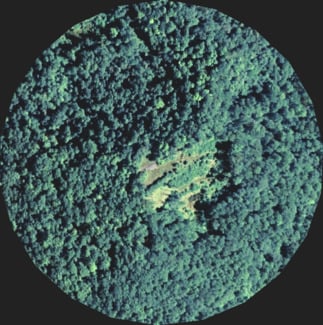

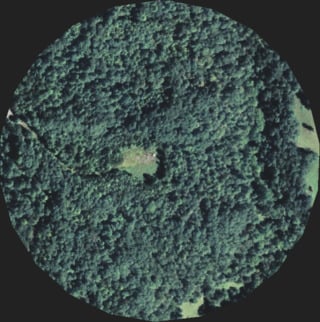

Explore the Pads

Use the menus and filters below to explore nearly 1,500 pad locations for permitted wells. If a well pad isn't visible in one of the images, the image may have been taken before construction or because gas producers have not yet built a well pad. Read our full methodology. ↓

Or, see all pads run by EQT Production Company or Antero Resources. See pads in Wetzel, Doddridge or Harrison counties.

Sources: West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) via Google Earth Engine

Methodology: To create individual images of every natural gas well pad in West Virginia, we downloaded a West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection database that included latitudes and longitudes on all permitted horizontal wells. Then, we used a clustering algorithm to group them by proximity.

We then collected aerial images taken by the USDA's National Agriculture Imagery Program within a 250-meter radius of the center of those clusters. We used Google Earth Engine to access and process the imagery. The NAIP images were originally captured between 2016 and 2018. In addition to a manual review, we also wrote code to check that no individual wells were duplicated in two separate images.

As of 2018, West Virginia has issued over 5,000 horizontal well permits. Clustering them together identified 1,470 locations where well pads have been or could be built. A manual review of the satellite images for those locations shows that around 630 already have clear and noticeable well pads. In the remaining 840 sites with permitted wells, many show that the area has been cleared and some construction has started. It is also possible that a well pad was constructed after the most recent NAIP image available was captured.

Note: If two distinct well pads are built close enough together, they may appear as a single image in our database.