Elijah Harris, 38, was living in a tent near Hollywood in January when Los Angeles sanitation workers showed up late one morning. Harris said he left to warn others nearby that the city was clearing the area. He came back to find his tent and its contents gone. He lost everything he needed for his job with DoorDash: his electric bike, ID and iPhone.

Losing his phone meant he had to regain access to his DoorDash account. Without his passport and Social Security card, which he said were also taken, that process proved difficult.

“They ask you to take a picture of the front and back of your ID and then take a selfie to verify it’s you, but I couldn’t do that,” Harris said. “It was a disaster.”

He said he couldn’t do his delivery job for months and then had to ride a nonelectric bike, which limited the area he could deliver to and the amount he earned.

Los Angeles officials did not comment on Harris’ case but said in a statement that the city “works to not unnecessarily remove anyone’s belongings” and that unattended items are stored or thrown away.

Harris is one of thousands of people living on the streets in the United States who have been subject to sweeps, the term often used to describe how cities dismantle homeless encampments or clear areas where people are living outside.

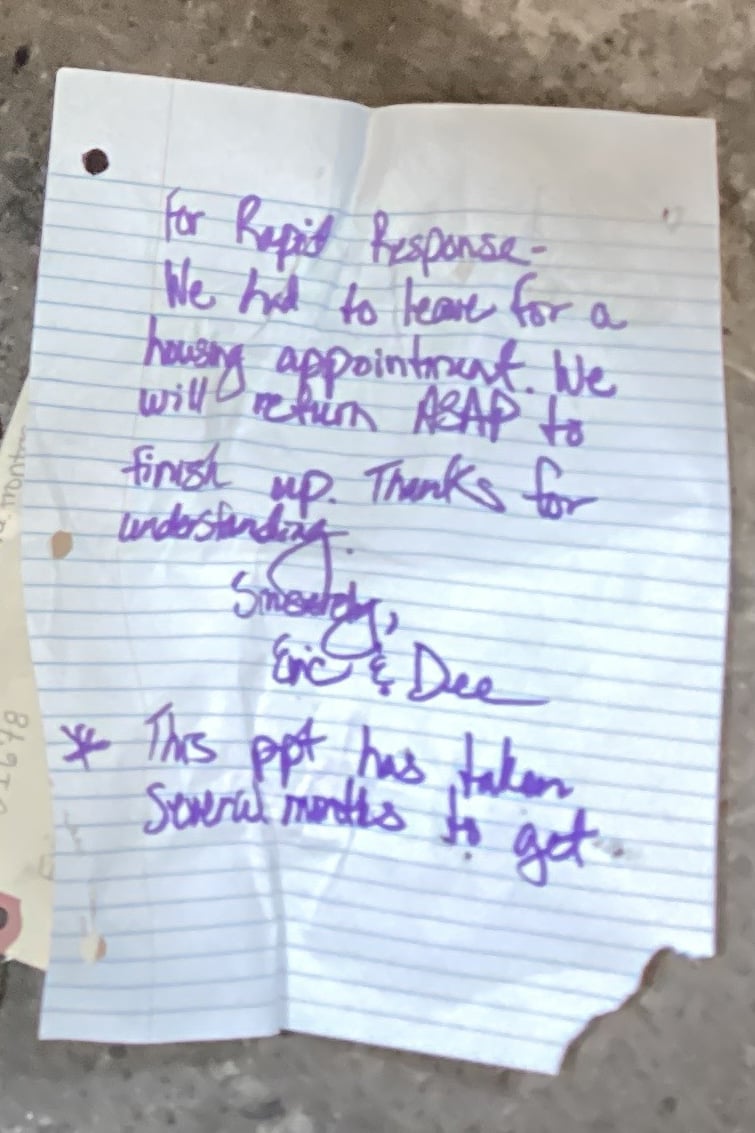

Cities, including Los Angeles, have policies to alert people before a sweep. In an ideal scenario, city officials said, people would be packed before crews arrive. But advance notice is not always required. Many people told ProPublica they didn’t know workers were coming or had stepped away for work, appointments or to find water when workers came. Some were in the process of moving their items but couldn’t do so quickly enough. Workers sorted through what’s left, sometimes storing items and throwing others into garbage bags or trucks.

Encampment removals have become more common as local governments try to reduce the number of people living on sidewalks and in other public spaces. They are likely to escalate further after a U.S. Supreme Court decision in June allowed municipalities to arrest or cite people for sleeping on public property even if there’s no available shelter.

Municipalities are often under pressure from business owners and residents to remove encampments, which officials said can obstruct sidewalks and pose public health, safety or environmental hazards.

Many cities told ProPublica that letting people live outside is not compassionate. “We cannot allow unsheltered residents to live in conditions that are below what we would accept for ourselves,” a Minneapolis spokesperson said in a statement to ProPublica.

Some cities, including San Francisco, characterized encampment removals as a first step toward shelter and housing.

“We are going to make them so uncomfortable on the streets of San Francisco that they have to take our offer” of shelter or housing, San Francisco Mayor London Breed said in July after announcing more aggressive sweeps would take place.

Advocates and people living on the streets say encampment clearings perpetuate homelessness.

“Every time someone gets swept, it just sets us back like 10 steps,” said Duke Reiss, a peer support specialist at Blanchet House in Portland, which provides meals and services to those experiencing homelessness. “It makes it almost impossible to get people help because everything requires documentation.”

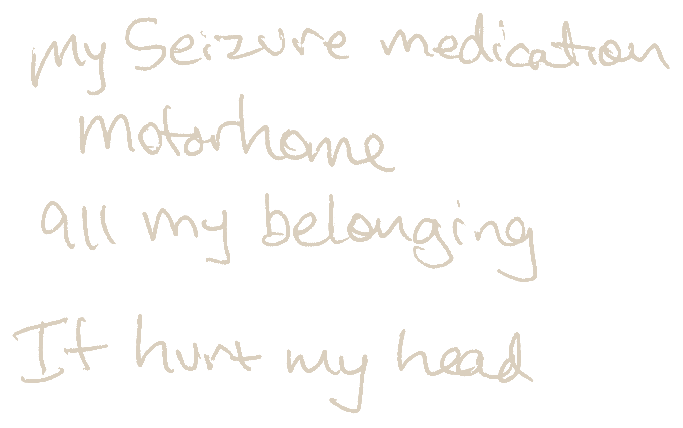

While many cities instruct workers to store identification, service providers told ProPublica about people they were working with who struggled to access Medicaid, disability benefits, food stamps, sobriety programs and housing after their documents were confiscated in encampment removals.

Courts have ruled that the destruction of property during sweeps violates the Fourth and 14th amendments, which prohibit unreasonable seizures and guarantee due process and equal protection under the law.

Some U.S. cities have established programs to store belongings — sometimes in response to those lawsuits. But they still have broad discretion over what ends up in the trash. ProPublica found that even when objects taken from encampments are stored, people are rarely reunited with their belongings.

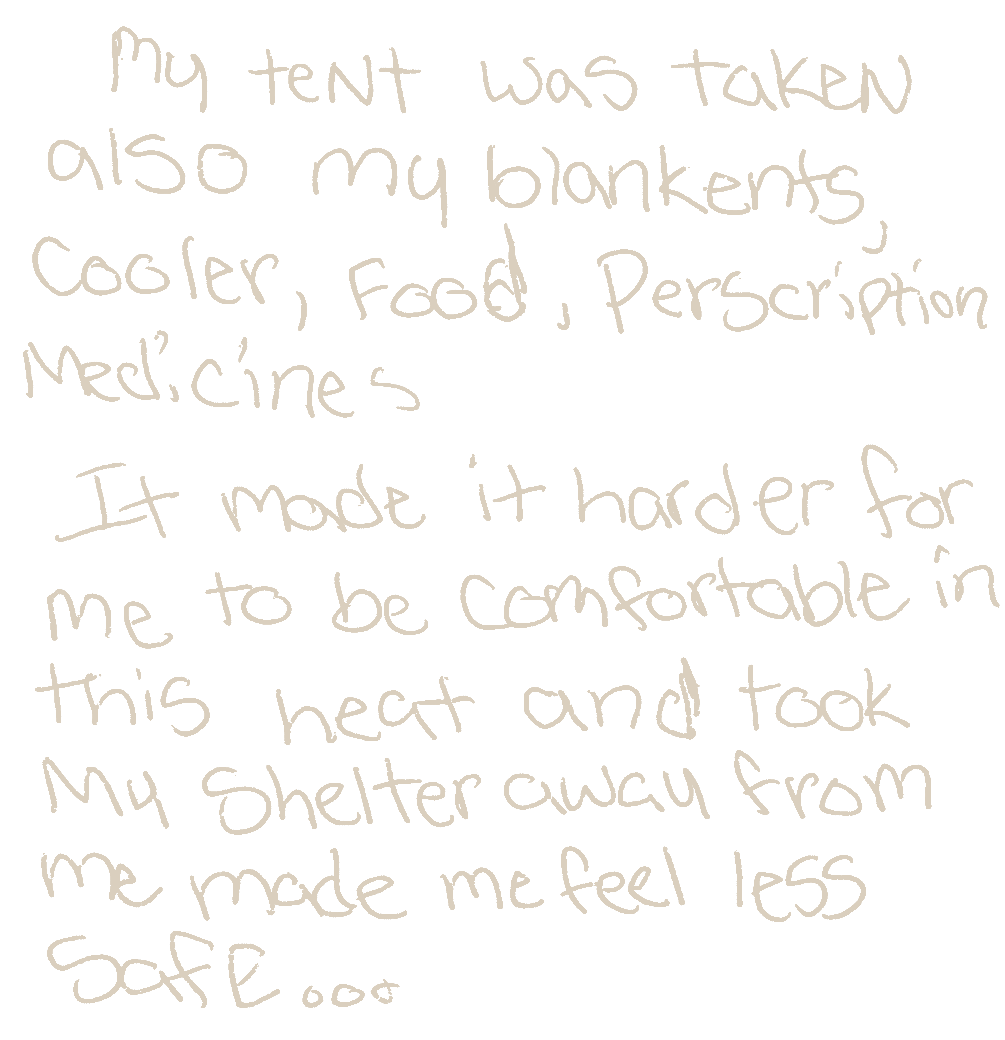

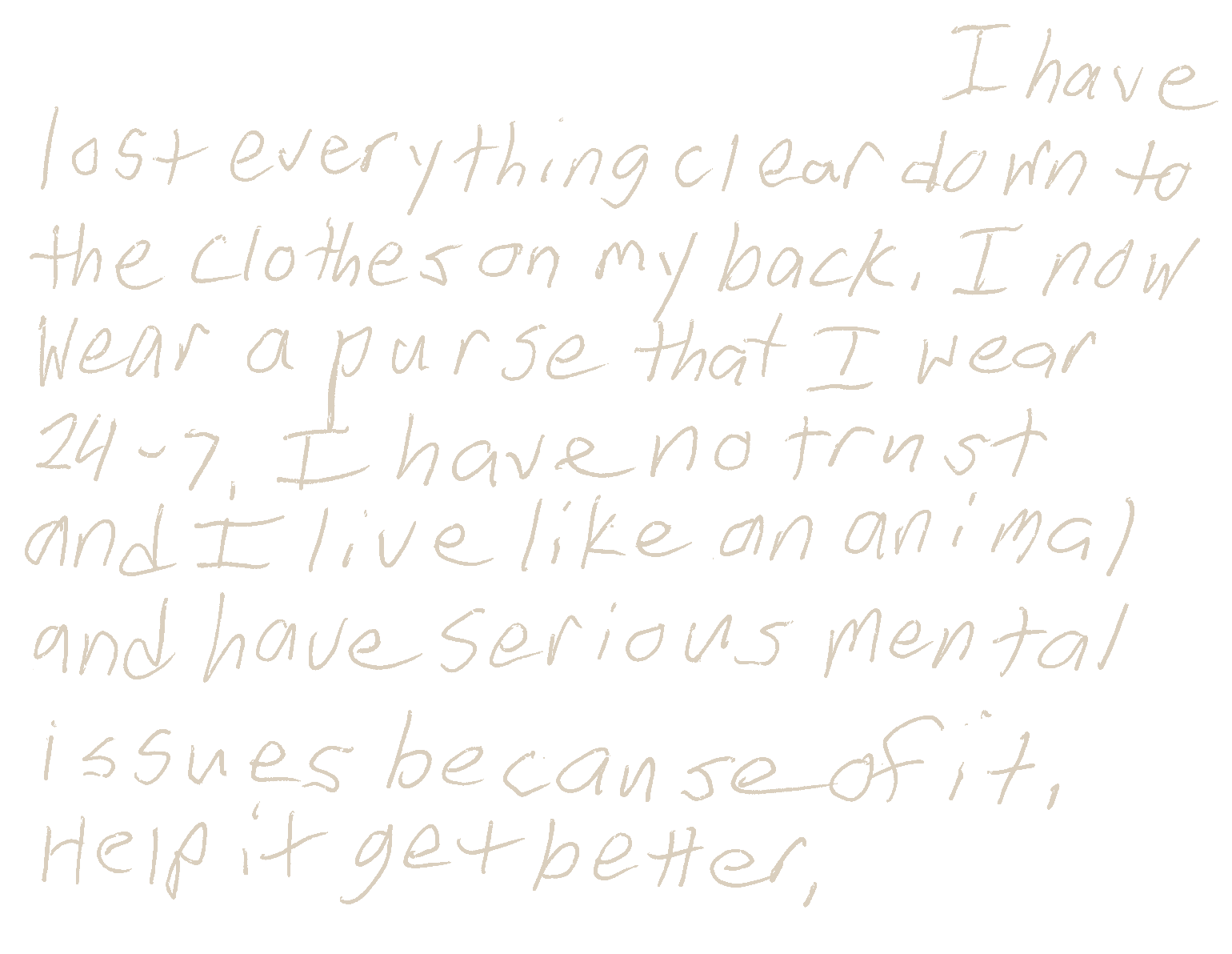

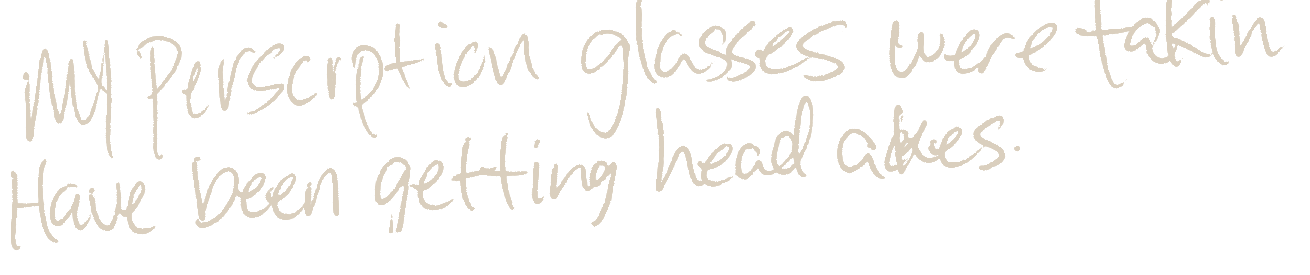

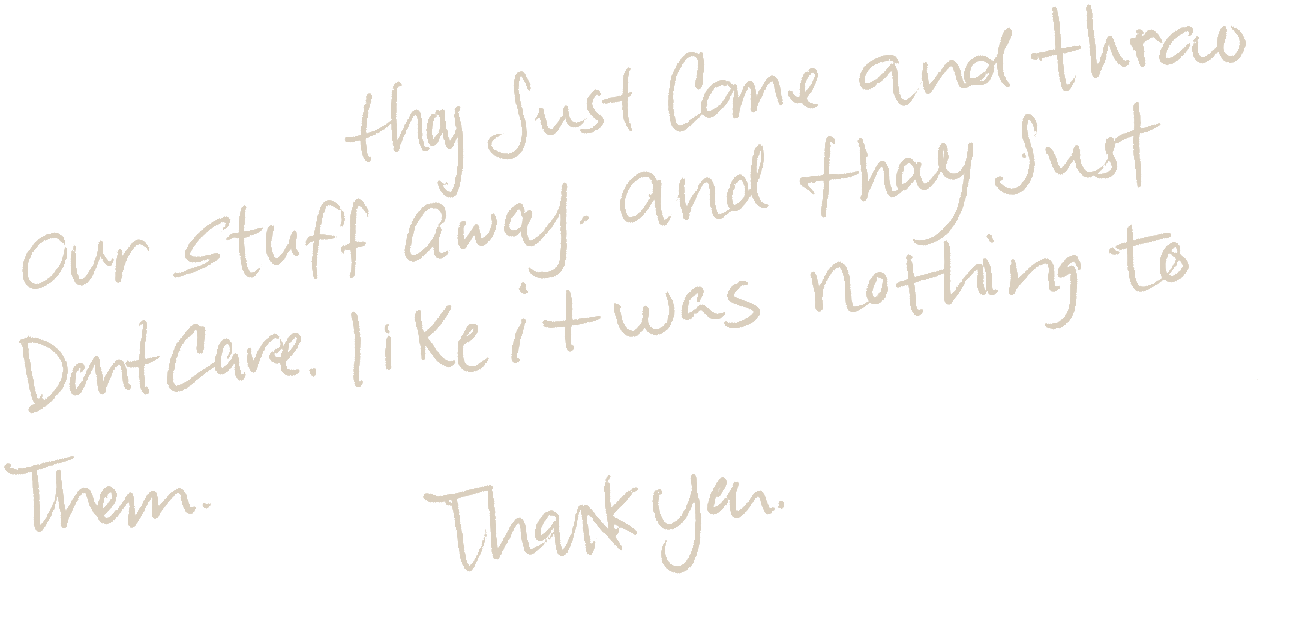

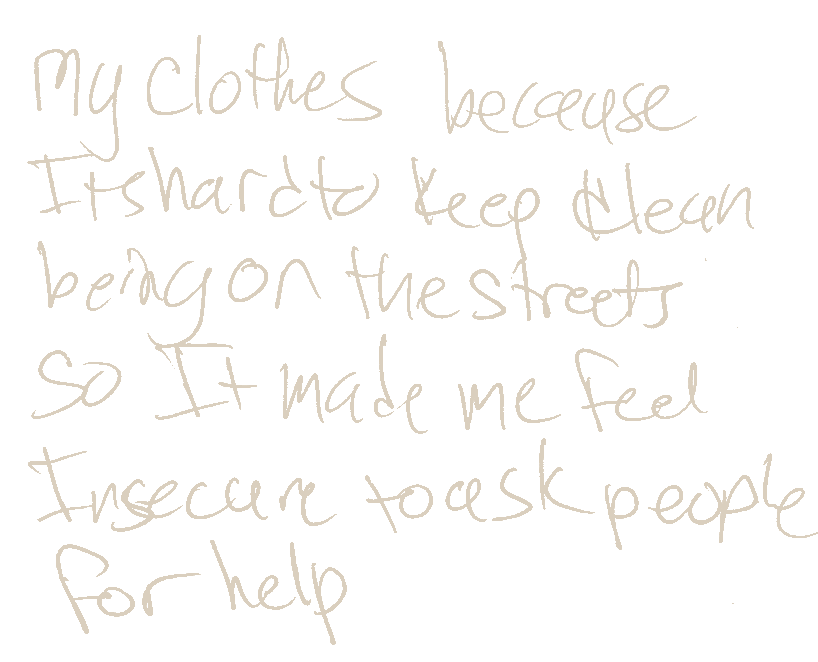

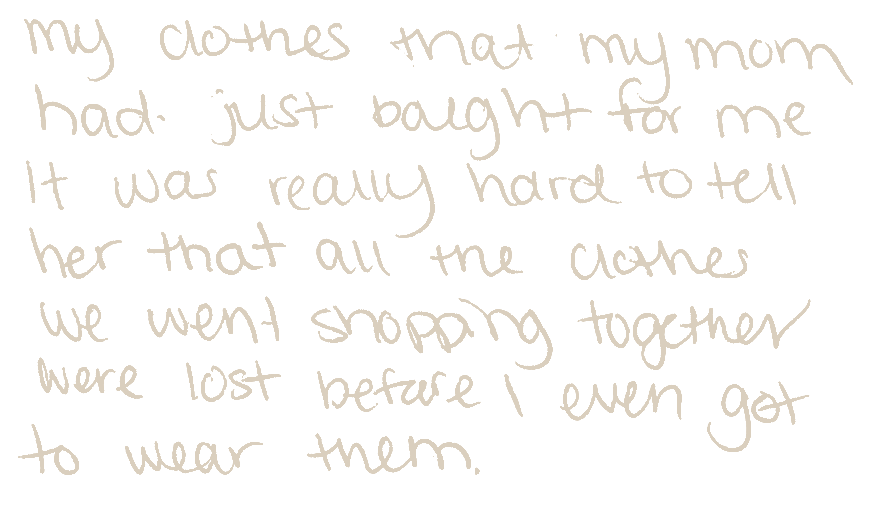

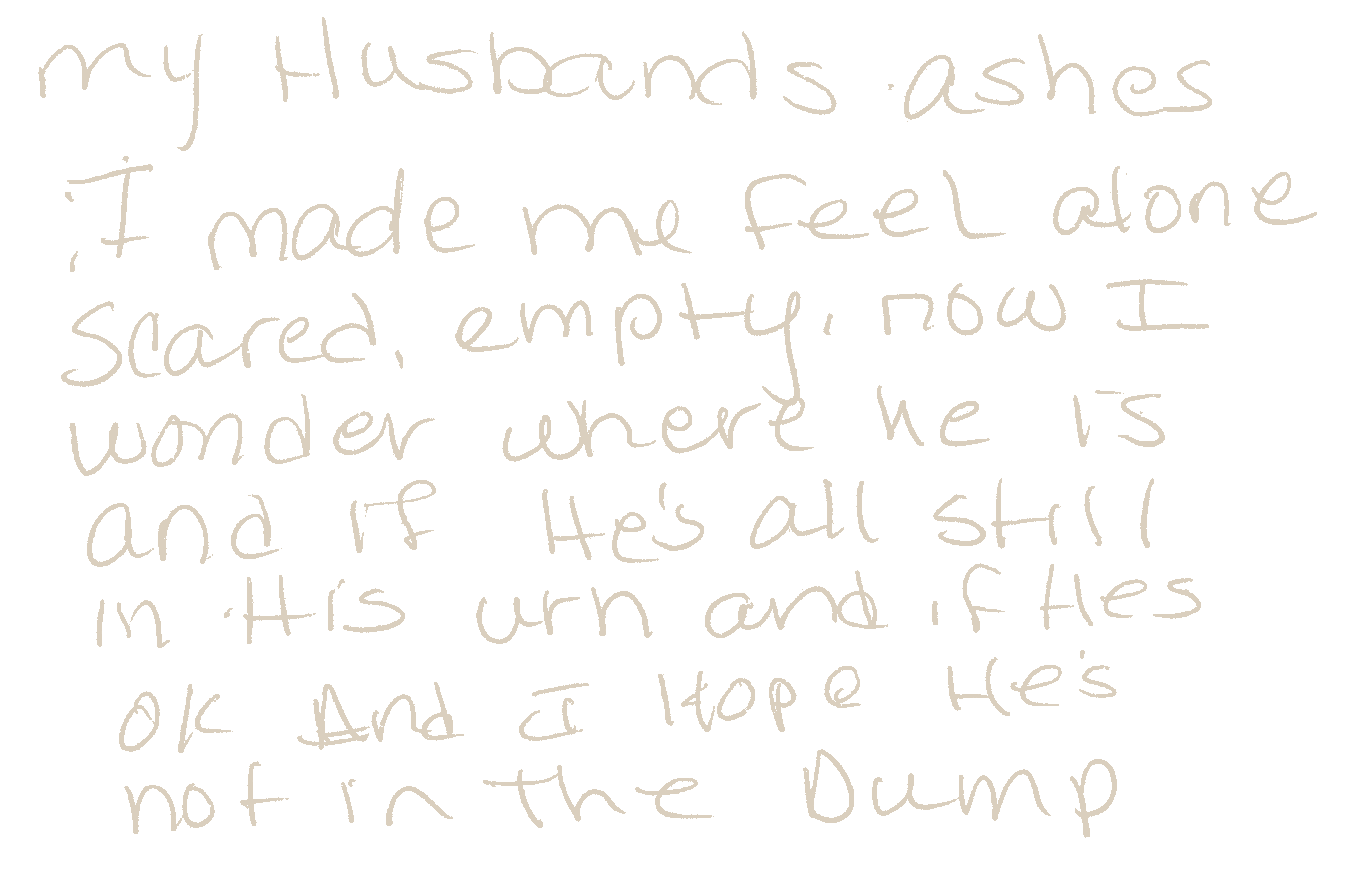

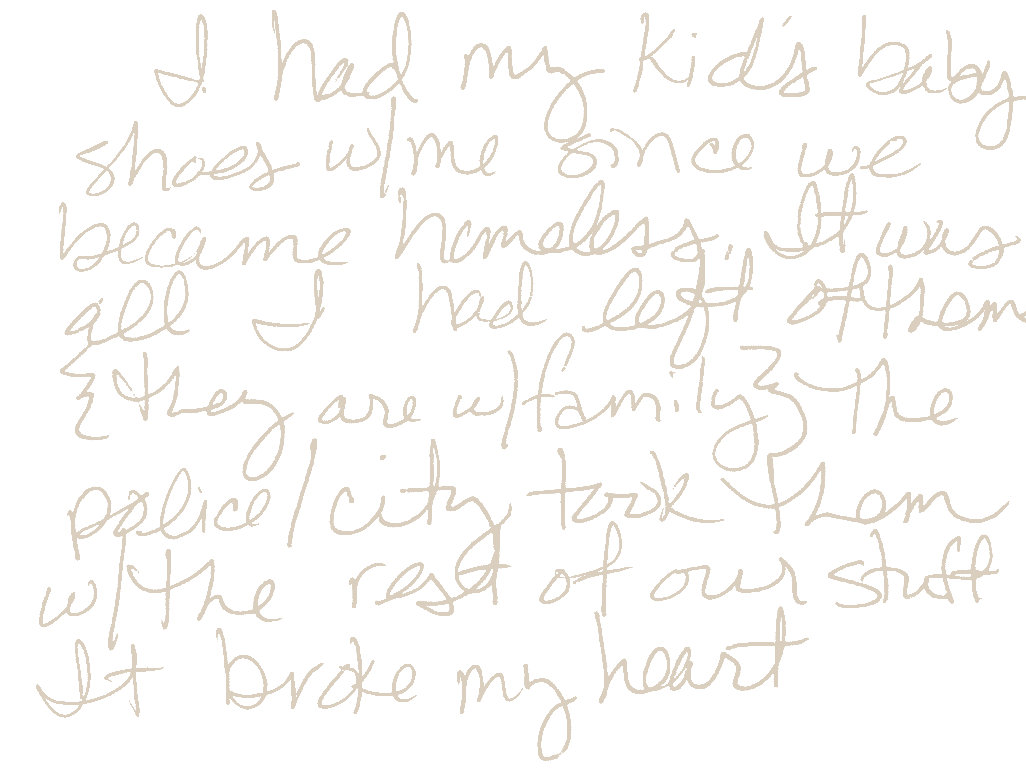

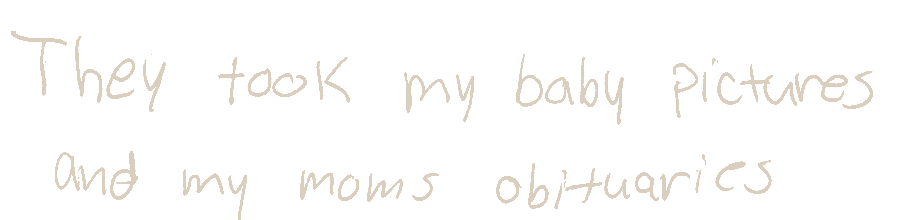

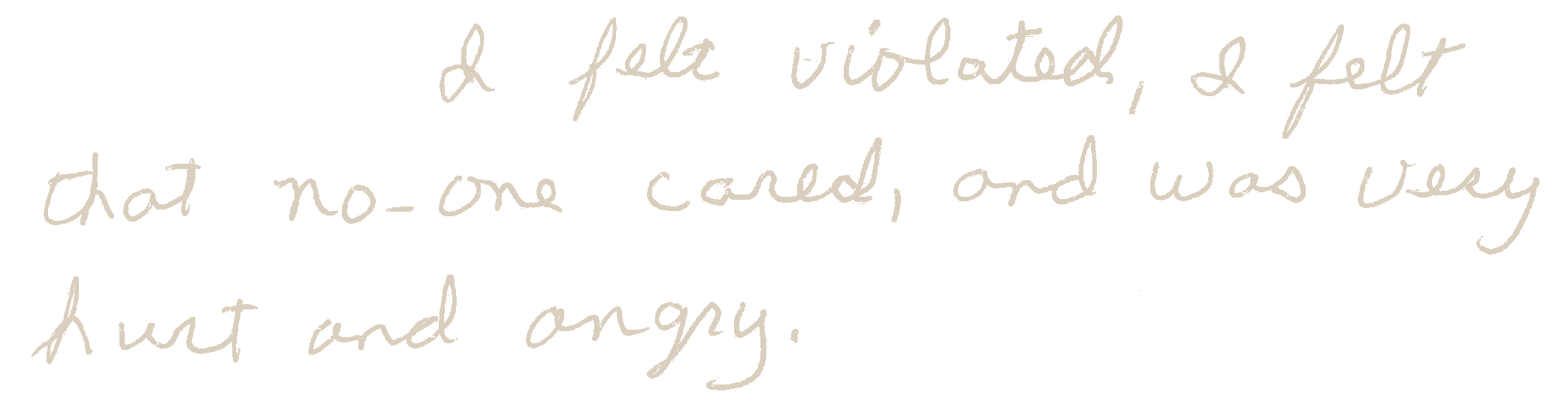

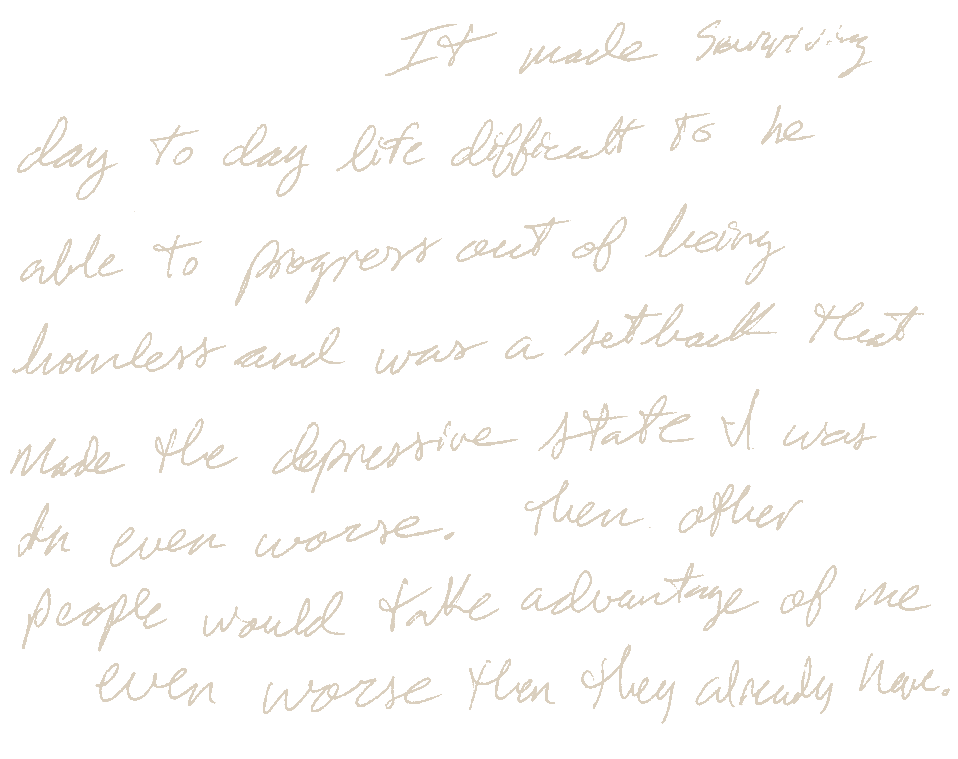

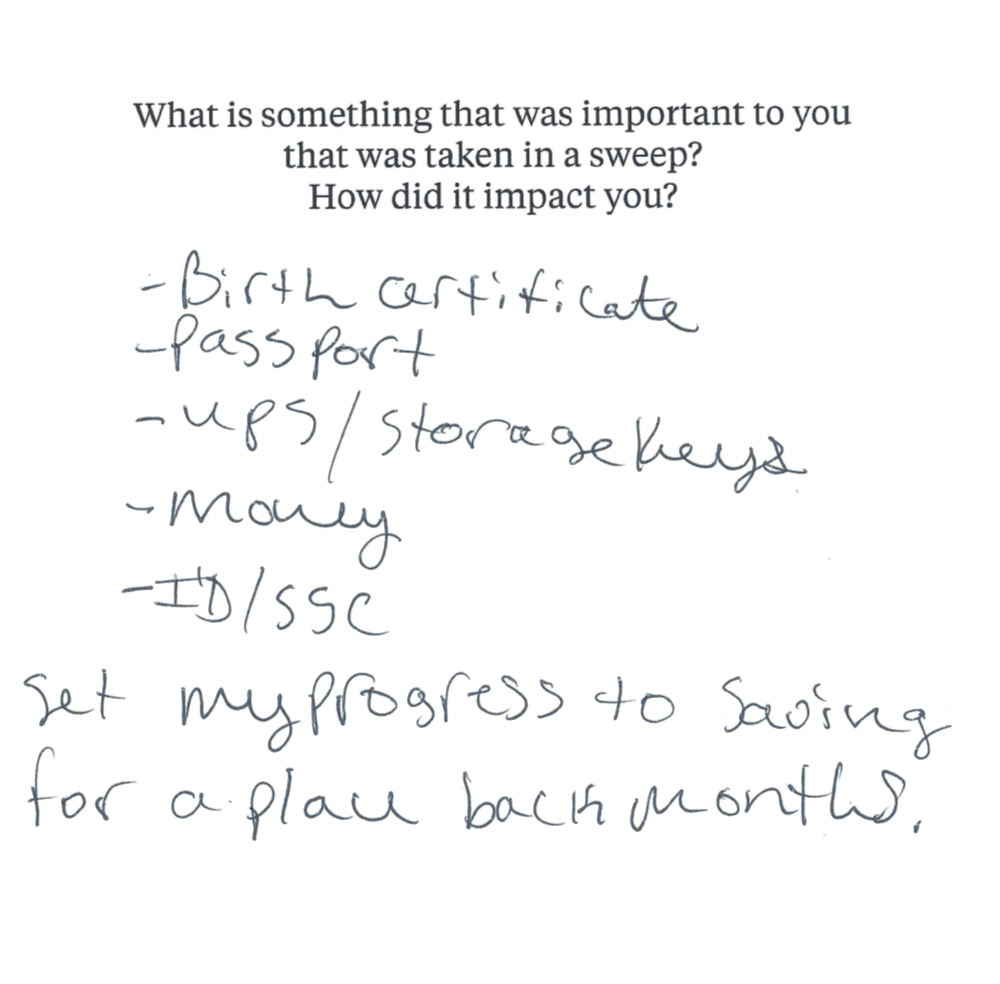

To understand what governments confiscate and how it impacts people living on the street, we received storage records from 14 cities with large homeless populations and reported on the ground in 11 cities. We spoke to 135 people who had experienced sweeps, and we gave many notecards to write about the consequences in their own words.

Over and over, they told ProPublica that having possessions taken traumatizes them, exacerbates health issues and undermines efforts to find housing and get or keep a job. More than 200 additional people who went through sweeps, outreach workers and others who have worked with unhoused people wrote to us echoing these sentiments.

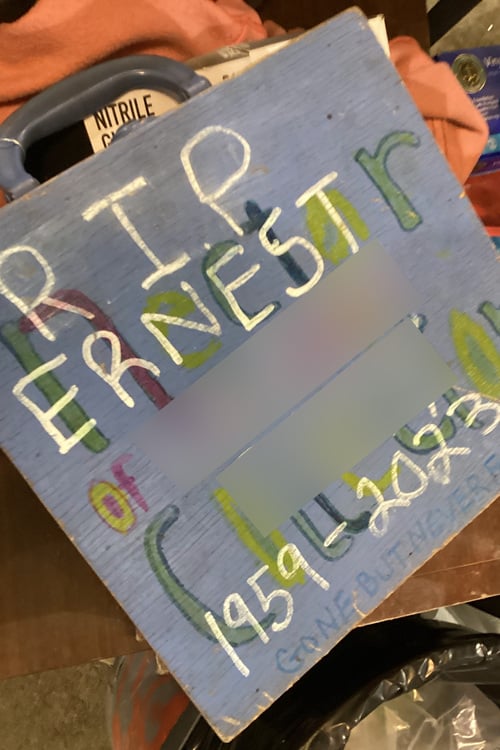

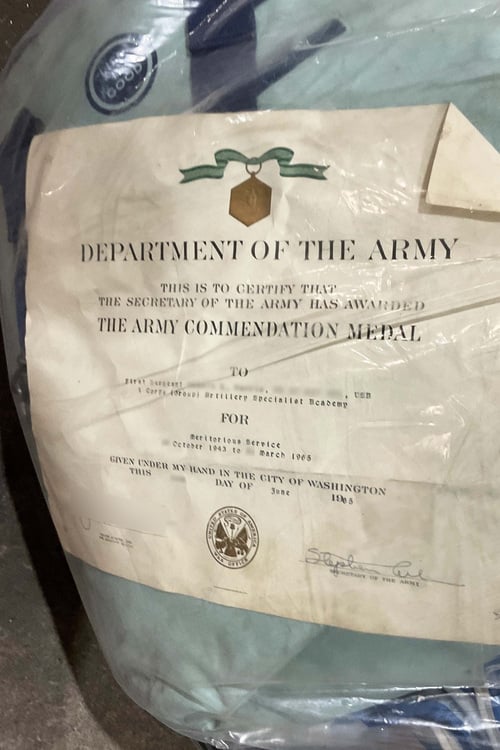

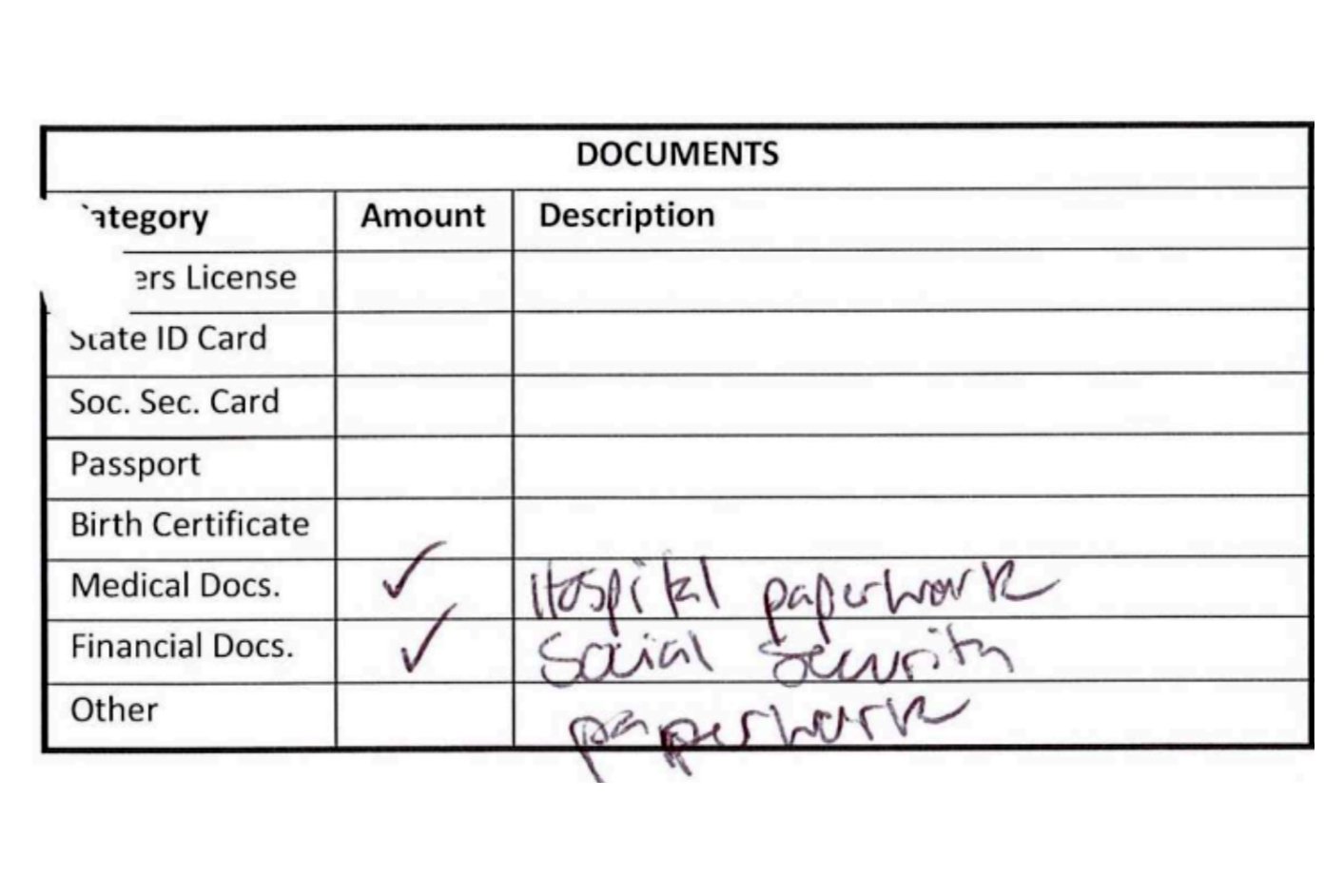

The storage records included images and written descriptions of the items cities had collected. Some records described the brand or color of belongings. Others had little detail, referring to most belongings as a “personal item” or providing no description at all.

Here are just some of the items that were taken.