Tennessee law prohibits women from having abortions in nearly all circumstances. But once the babies are here, the state provides little help. We followed one family as they struggled to make it.

The Year After A Denied Abortion

When she got pregnant, Mayron Michelle Hollis was clinging to stability.

On Dec. 21, days after returning home from the hospital, Mayron was arrested.

The arrest depleted any savings Mayron and Chris had put aside to take off work for Elayna’s first weeks. Now they were in debt.

Chapter One A New Life, in Limbo

Chapter Two Elayna Comes Home

Chapter Three Gravitational Pulls

Chapter Four A Family on the Edge

When she got pregnant, Mayron Michelle Hollis was clinging to stability.

At 31, she was three years sober, after first getting introduced to drugs at 12. She had just had a baby three months earlier and was working to repair the damage that her addiction had caused her family.

The state of Tennessee had taken away three of her children, and she was fighting to keep her infant daughter, Zooey. Department of Children’s Services investigators had accused Mayron of endangering Zooey when she visited a vape store and left the baby in a car.

Her husband, Chris Hollis, was also in recovery.

The two worked in physically demanding jobs that paid just enough to cover rent, food and lawyers’ fees to fight the state for custody of Mayron’s children.

In the midst of the turmoil in July 2022, they learned Mayron was pregnant again. But this time, doctors warned she and her fetus might not survive.

The embryo had been implanted in scar tissue from her recent cesarean section. There was a high chance that the embryo could rupture, blowing open her uterus and killing her, or that she could bleed to death during delivery. The baby could come months early and face serious medical risks, or even die.

But the Supreme Court had just overturned Roe v. Wade, which guaranteed the right to abortion across the United States. By the time Mayron decided to end her pregnancy, Tennessee’s abortion ban — one of the nation’s strictest — had gone into effect.

The total ban made no explicit exceptions — not even to save the life of a pregnant patient. Any doctor who violated the ban could be charged with a felony.

Women with means could leave the state. But those like Mayron, with limited resources or lives entangled with the child welfare and criminal justice systems, would be the most likely to face caring for a child they weren’t prepared for.

And so, the same state that questioned Mayron’s fitness to care for her four children forced her to continue a pregnancy that risked her life to have a fifth, one that would require more intensive care than any of the others.

Tennessee already had some of the worst outcomes in the nation when measuring maternal health, infant mortality and child poverty. Lawmakers who paved the way for a new generation of post-Roe births did little to bolster the state’s meager safety net to support these babies and their families.

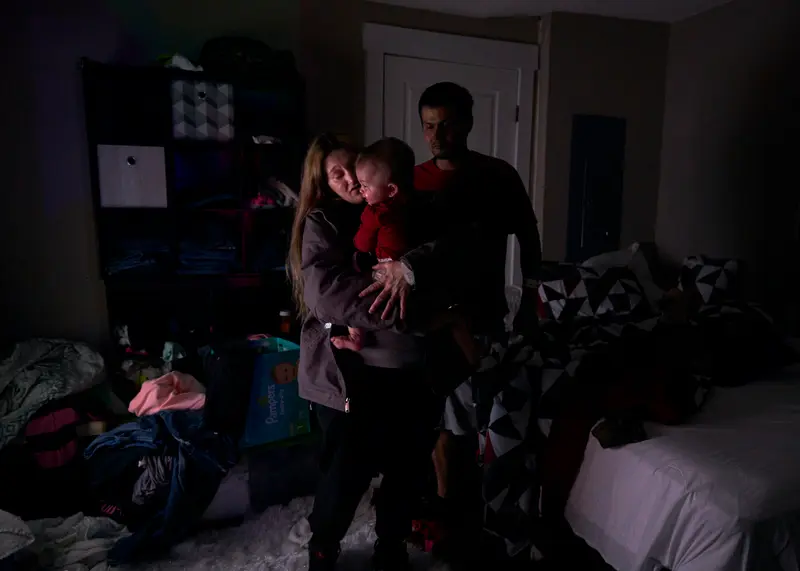

In December 2022, when Mayron was 26 weeks and two days pregnant, she was rushed to the hospital after she began bleeding so heavily that her husband slipped in her blood. An emergency surgery saved her life. Her daughter, Elayna, was born three months early.

Afterward, photographer Stacy Kranitz and reporter Kavitha Surana followed Mayron and her family for a year to chronicle what life truly looked like in a state whose political leaders say they are pro-life.

Born weighing less than 2 pounds and unable to breathe on her own, Elayna would need months in the neonatal intensive care unit. Her stay came with an estimated six-figure bill and was covered by the state-managed Medicaid program.

On Dec. 21, days after Mayron was discharged from the hospital, she was arrested.

She had thought the case related to leaving her daughter in the car was resolved when state child welfare officials closed the matter. But prosecutors had separately filed a felony criminal charge. The penalty is eight to 30 years in prison.

She paid a $6,000 bond to be released from jail and found a lawyer willing to represent her for a $6,000 fee by payment plan.

The arrest had depleted any savings she and Chris had put aside to take off work for Elayna’s first weeks. Now they were in debt.

Mayron, who was still recovering from a lifesaving surgery that removed her uterus, returned to work as an insulator apprentice two weeks later.

Her husband, Chris, also had to work. Neither of them had paid parental leave.

Safety Net Parental Leave

Research indicates access to paid family leave is linked to a decrease in infant deaths and better economic, physical and mental health for new parents.

Currently, 13 states have some form of paid parental leave to care for newborns.

No states that banned abortion offer paid parental leave.

There were no facilities equipped to handle Elayna’s needs in their county.

So Elayna spent many of her earliest moments without her parents, in a hospital an hour away.

Charities offer free housing near the hospital for parents of some children in the NICU. Mayron called nearly every day after her daughter was born, but none had any openings for weeks.

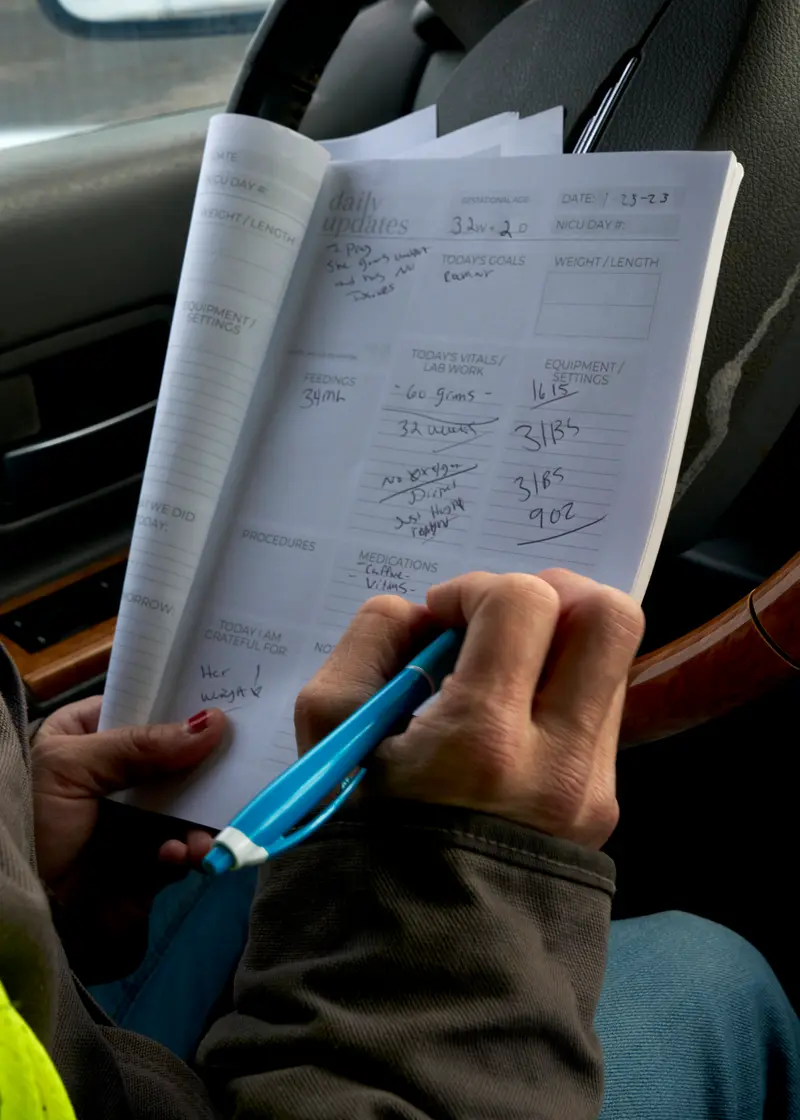

After her 10-hour shifts, Mayron visited Elayna as often as she could, sometimes sleeping in her car in the hospital’s parking garage.

While Elayna remained in the hospital, the family was eligible for disability payments from the federal government for having a child born weighing less than 2 pounds. They amounted to $30 a month.

Mayron wasn’t sure how to access them — but they wouldn’t even cover a week of gas money to and from the hospital anyway.

Mayron brought Elayna home in late February, on her daughter Zooey’s first birthday.

But Elayna’s health was still fragile. Twice in the first month she was rushed back to the hospital because of lung infections.

Once home, her medical needs were complex. She had a feeding tube, breathed with the help of a machine and needed to see a pediatrician, an eye doctor, a lung specialist and an occupational therapist.

Mayron quit her job to navigate Elayna’s care.

Donations to Mayron’s GoFundMe after ProPublica wrote about her story helped the family keep up with rent, lawyer and court fees, debt, gas and baby supplies for a few months.

Mayron filled out paperwork to get help to pay for her daughter’s needs. She knew Elayna should have been eligible for disability support, given her premature birth and developmental challenges. But none of the phone calls she made or forms she submitted seemed to lead to any aid. It would be almost a year before Mayron received a letter that said Social Security approved $914 per month in disability payments for Elayna. It retroactively covered February to August but was cut off after that with no explanation. The family has never received any of the money.

Mayron knew she was supposed to qualify for at-home help from a nurse while Elayna was on the feeding tube, and she asked the hospital for assistance setting it up when she was going home. But she ran into issues getting her insurance to approve it. In the end, it was too late: A nurse finally showed up for a visit two days after Elayna was already taken off the feeding tube.

Mayron decided not to apply for unemployment. She didn’t understand the rules and felt it would be too risky. She had applied for unemployment while she had to take leave for her high-risk pregnancy with Elayna, but a mistake on the paperwork later meant she had to pay back some of the money with fees. She also didn’t qualify for disability support because her complications from the surgery were considered short-term and partial.

The new financial needs were crushing.

By late spring, Mayron and Chris’ bank account balance was dwindling to the hundreds. They began to fall behind on their $1,400 monthly rent and $550 car payments.

Their cars kept breaking down. Chris needed a reliable truck for the business he runs installing vinyl siding. They saw a special offer for financing, so they went to a dealership to see if they could get a new one. They had been using a $400 credit card to build up credit and Mayron’s score was above 700, but their history was too short and they didn’t qualify for a loan.

More credit card offers kept arriving in their mailbox. The couple applied for them and other loans and bought used cars at double-digit interest rates so they could get to work.

After Elayna came off the feeding tube in May, they decided Mayron needed to go back to work. She could make about $600 a week installing insulation. But first they had to figure out child care. Elayna was still too fragile for full-time day care. According to care.com, an experienced nanny in their city would cost about the same as Mayron’s weekly paycheck.

On Facebook, they found a 24-year-old babysitter who charged $250 a week to watch the two girls.

Safety Net Child Care

In 2019, nearly half of Tennesseans lived in a child care desert, an area that has three times as many children as licensed child care slots. In Mayron’s city, Clarksville, more than 3,000 children in 2023 qualified for government assistance for child care, but 941 were unable to access it.

Between 2011 and 2020, 13 bills aimed at alleviating child care burdens were proposed in the Tennessee legislature. All of them failed.

Mayron would leave for work at 4:45 a.m.

Chris would watch the girls until the babysitter arrived, around 7 a.m. Then, he headed to work too.

Mayron returned every night after 5 p.m., often covered in fiberglass, then launched into cleaning the house and the evening routine with her girls.

After four months, Mayron got connected with an early intervention program that could provide free virtual therapy to support Elayna’s movement and development.

Safety Net Early Intervention

Children born preterm are at risk for developmental delays and disabilities, and all states have free or reduced-cost programs to provide support. Yet researchers say not enough low-income families are able to access those programs. Many states don’t actively connect children with these services because their programs aren’t well-funded, they say.

In Tennessee, less than 3% of eligible children in low-income families are enrolled in evidence-based home visiting programs, one of the lowest rates in the country.

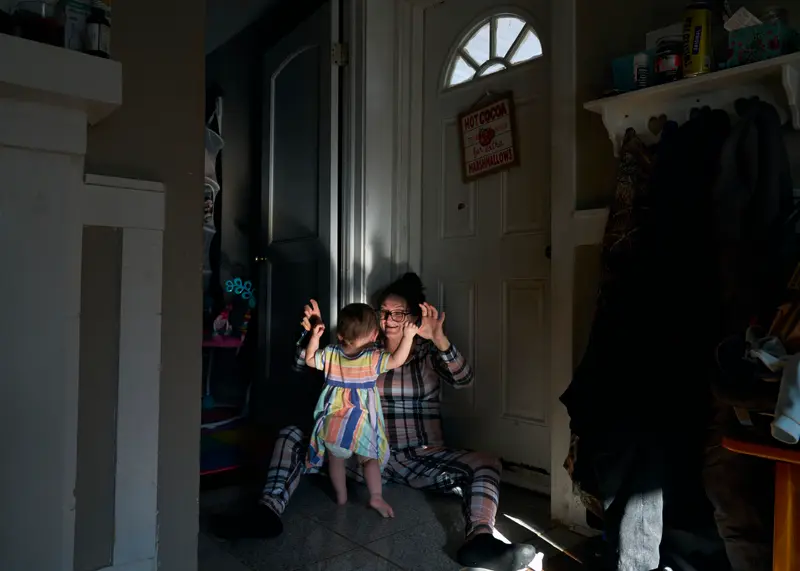

By summer, Elayna was getting stronger each day and Zooey was getting into everything.

Mayron and Chris started dreaming of a house for their girls. One that didn’t have a rusted bathtub, mice infestations and heat that broke down in the winter. They also wanted to move away from neighbors who frequently overdosed, a stressful reminder of their past.

Mayron was at work in June when she got a call from the babysitter. Sheriff’s deputies had arrived at the door with an arrest warrant.

Mayron thought the case related to leaving Zooey in the car was still working its way through the courts. She didn’t understand why she was being arrested again.

She was afraid things would escalate and drag her back into a costly legal battle. A conviction — or worse, a prison sentence — could mean losing the girls. Just fighting it could push them further into debt.

That afternoon, she stopped at a bar for a drink. Alcohol was never her drug of choice, she said. She told herself she could handle a few drinks while she figured out her next step.

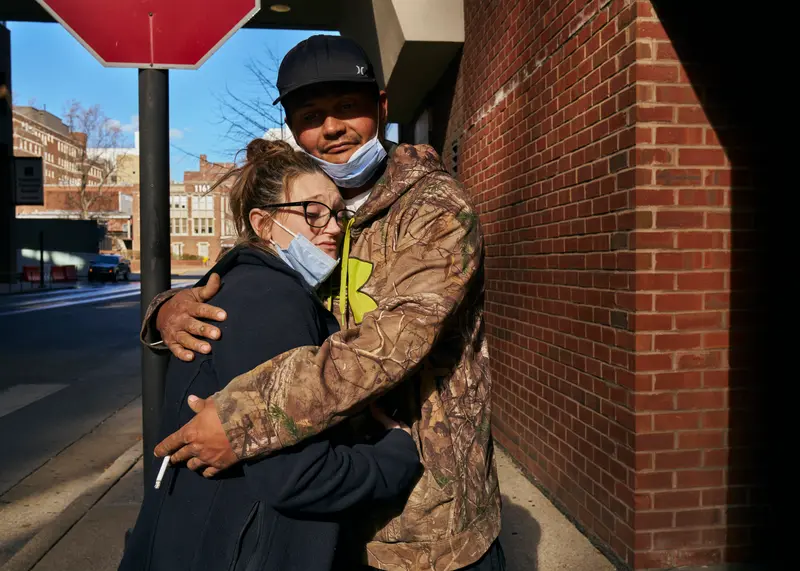

After speaking to a lawyer, Mayron prepared to turn herself in, kissing her babies goodbye.

She was told the arrest was necessary because the district attorney’s office had downgraded her charges to a misdemeanor. Sheriff’s deputies booked her into jail and quickly released her.

Mayron returned home to a sick baby: Elayna had another fever, so Mayron put her on the oxygen machine and waited for the doctor to call her back.

When she returned to court a month later, Mayron’s lawyer had negotiated a deal. To stay out of jail, Mayron pleaded guilty to reckless endangerment in exchange for one year of probation.

The outcome provided little comfort. Mayron knew any involvement with the criminal justice system could make it harder to provide for her family — she might need to miss work for probation check-ins and drug tests — and easier for her kids to get taken from her again if she made any more mistakes.

She worried what authorities would think about delta-8, the legal cannabinoid she used to calm her nerves.

To avoid it, she feared she’d end up turning more to alcohol.

Then, summer brought more people to care for.

After losing her housing in August, Mayron’s mother moved into the cramped two-bedroom house.

Mayron’s mother shared a drafty second-floor room with Mayron’s father, her ex-husband, who also stayed with them.

Health issues kept Mayron’s mother mostly bed-bound. Her father often spent his nights drinking with the neighbors.

Tension led to fights.

Mayron was struggling to cope with the pressure. She took medication to help with ADHD and suboxone for substance use disorder. In the past, she had tried some depression and anxiety medications prescribed by her doctors, but they made her feel sleepy and lethargic, so she didn’t continue. Other medications were off limits because of her addiction history.

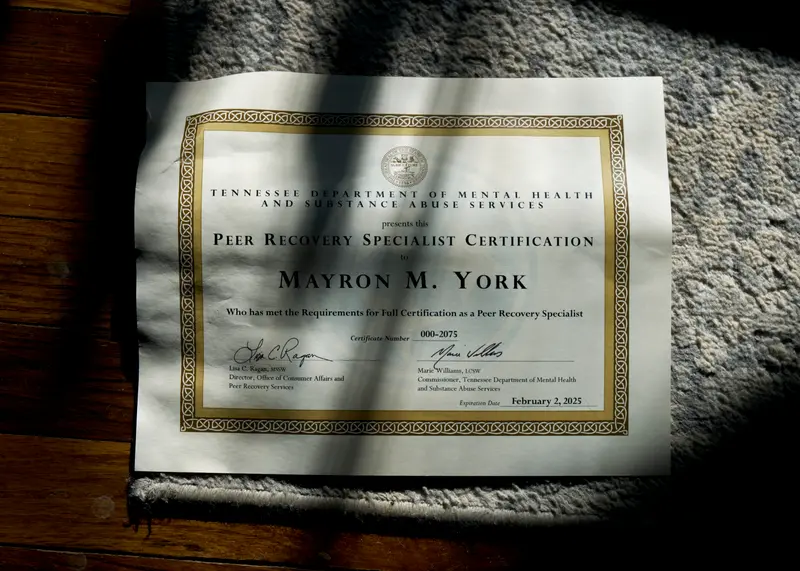

She had once hoped to find a job helping other mothers with substance use disorder, volunteering to lead Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and even earning a peer recovery specialist certificate while Elayna was in the hospital.

Now her own recovery was at risk.

Throughout the turmoil, Mayron and Chris had been able to keep a roof over their heads and put food on the table.

By September, both were in peril.

Their landlord threatened eviction for late payments.

Their credit cards and loans were spiraling out of control. Besides paying off the cars for work, Chris sometimes used them to buy tools and to cover his workers’ salaries. Mayron used them to buy groceries and to make the house more comfortable. Soon they were nearly $40,000 in debt and their credit score had dropped about 200 points. Mayron was devastated when she finally realized the extent of it — there was no hope of achieving their dream to buy a house anytime soon, or even move.

They also learned they were losing their food stamps — $972 a month. Since Mayron went back to work, their income one month put them above the eligibility limit of $39,000 a year, before taxes, for a household of four.

Both their jobs were unpredictable, and the aid had been crucial to help them stay stocked with formula and baby food the past year.

Safety Net Government Assistance

In Tennessee, a family of four making less than $39,000 a year should be eligible for food stamps if their current bank balance is under $3,001 and they share their household with a person over 60 or with a disability.

Tennessee’s child poverty rate ranks among the worst in the nation, in part, because families who qualify for government help aren’t getting it. About 1 in 10 families eligible for food stamps aren’t receiving them. According to researchers, the program requirements are too punitive and complicated, leaving such families shut out.

In 2019, the state was holding nearly $800 million in unspent federal funding designated for temporary assistance to needy families. Since then, monthly benefits for eligible Tennesseeans have barely risen, from $277 to $387 in 2021. That ranks among the lowest in the nation for temporary cash assistance.

In her lowest moments, Mayron felt she was failing her daughters. “I felt like: I’m not good enough to have them,” she said. “Like, I can’t afford them, because I can’t get them the things I want them to have.”

Mayron started meeting up with co-workers for drinks after work more often.

Then, Mayron’s temporary insulation gig finished and she was out of work. She would have to reapply for food stamps for the new year and wait months to see if they would be reinstated.

As fall closed in, Mayron started having panic attacks and her health declined. She lost weight and barely slept.

Ever since her traumatic C-section, she noticed she no longer had any feeling when she went to the bathroom. Her stomach and back were sometimes numb or radiated pain. She knew doctors had removed her uterus, but she had never been totally clear about what had happened inside her body during the surgery or its long-term effects.

Mayron had state Medicaid insurance after Tennessee expanded coverage to women for one year after giving birth in 2022. But she was so consumed with holding things together, she never made time to see a doctor.

Mayron had a psychiatrist through a hospital research program for mothers in recovery for opioid addiction. When she could get an appointment, she talked with him about her ADHD medication over video calls, but she feared confiding in him about her stressors or the alcohol. She felt he would be too busy anyway.

Alcohol became a more frequent escape.

Sometimes it triggered her worst impulses.

Chris bore the brunt of her outbursts, especially over money.

Some days she raged from morning until night.

Chris had been dealing with his own mood swings and depression from not being able to provide for the family since Elayna’s birth. He usually kept quiet and retreated inside himself, but sometimes the stress broke through and he yelled back.

As the holidays approached, Mayron told Chris she wanted a separation.

Chris started to spiral. Two days before Thanksgiving, he relapsed.

The next week he checked into an inpatient mental health and rehab facility and stayed for a week.

“This all broke me,” he wrote as his reason for admission, after recounting the events of the past year. “None of this is my fault but I’ve got to deal with it all. I try not to be resentful with my wife. I have trouble paying attention to my family, I space out.”

While Chris was in inpatient care, one of the neighbors offered to help Mayron around the house.

She started to spend more time with him.

By the end of the week, she had slept with him.

When Chris came home the next week, he could see Mayron was unraveling.

The volatility reminded him of the times before they got serious about their recovery four years ago.

The family was supposed to go to church the next morning, but Mayron disappeared that night and no one knew where she was.

Chris took the girls anyway and tried to find a moment of peace as a family amid the chaos.

Mayron came home with a black eye. She couldn’t remember how she got it.

On Elayna’s first birthday, Dec. 13, Mayron and Chris fought all morning.

Mayron wanted Chris to go to work, since the family debt had grown while he missed jobs and was getting treatment.

He didn’t want to leave her alone with the kids in her current state.

Chris took the kids to the babysitter’s house.

That triggered her memories of other children who had been removed from her custody, years earlier.

Mayron exploded at him in the front yard.

Neighbors showed deputies a video of Mayron hitting Chris. She was arrested.

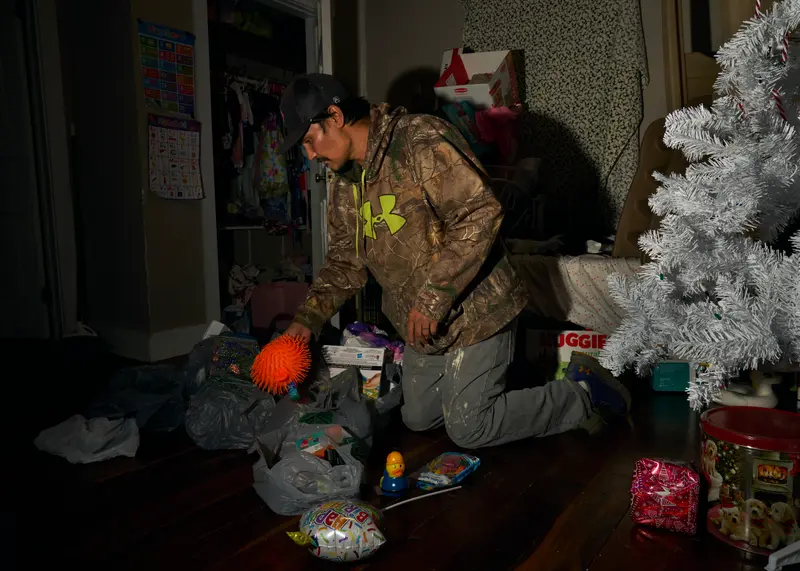

Chris knew Mayron had been planning to do something special to mark Elayna’s first year. She had already bought a tablecloth, sparklers and some toys from the dollar store.

Despite the turmoil of the year, it felt significant to recognize her daughter had come a long way:

From less than 2 pounds, hooked up to breathing machines, to a curious infant, cuddling with her older sister and trying to figure out how to walk.

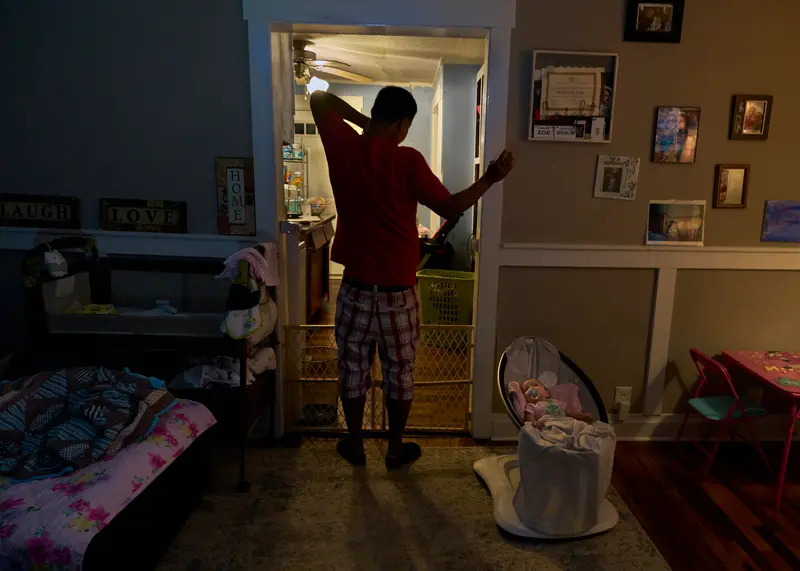

With Mayron in jail, the celebration fell to Chris. As the sun began to set, he cleaned the living room and kitchen, then went to Big Lots and chose gifts: a Stack and Play Rainbow Cloud and a Fisher-Price toy telephone.

He picked up his daughters from the babysitter’s house, then took them to Publix to get dinner: hot dogs, mac and cheese, french fries, two cakes — one with Elayna’s name on it and one to smash — and a “Happy Birthday” balloon.

At home, he cooked dinner and wrapped the presents, then searched everywhere for a special candle of the number 1 he remembered Mayron had bought. He never found it.

It was past 8 by the time Chris set Elayna up on her high chair so they could sing, making sure to have his phone ready to take videos so Mayron could watch them later. Mayron’s father joined to celebrate and Zooey danced to the music and played with the balloons. Then Chris set off a sparkler and let Elayna smash her cake.

Mayron sat up all night behind bars, on a hard bench, begging for an extra phone call home to wish her daughter a happy birthday.

Editor’s Note

Last year, ProPublica reported the story of how Mayron Hollis faced a life-threatening pregnancy under Tennessee’s abortion ban. Photographer Stacy Kranitz and reporter Kavitha Surana continued to follow the family for a year. The family shared medical records, court records, bank statements, receipts, bills and letters from state authorities and their landlord with ProPublica journalists and let them shadow their everyday lives. ProPublica fact-checked the details of the story with the family before publication.

Mayron said she let journalists document her life in intimate detail because she wanted people to “see for themselves and feel it in their own lives” her family’s struggles in raising two babies after a traumatic pregnancy and while recovering from a history of addiction.

“They forced me, basically, to have a child,” she said of the state after the abortion ban. But then, “they didn’t help me take care of that child.”

At the time of publication, the family was still struggling.

- Photography Stacy Kranitz

- Written and reported Kavitha Surana

- Additional reporting Stacy Kranitz

- Project editing Andrea Wise and Ziva Branstetter

- Photo editing Andrea Wise

- Additional photo editing Anna Donlan

- Story editing Alexandra Zayas and Ziva Branstetter

- Additional editing Boyzell Hosey and Tracy Weber

- Design and development Anna Donlan and Allen Tan

- Research Mariam Elba

- Copy editing Diego Sorbara

- Audience editing Kassie Navarro, Sophia Kovatch and Grace Palmieri